This page is based on an exhibit that the historical society did for the "Year of the Veteran" in 2018, which commemorated the centennial of the end of WWI. It covers Pine Plains' wartime experience from the American Revolution through WWI. It is not intended to be a comprehensive account of Pine Plains' service during these wars, and does not include wars or rebellions during this period (of which there are a surprising number) where we do not have a record of participation by any Pine Plains citizens.

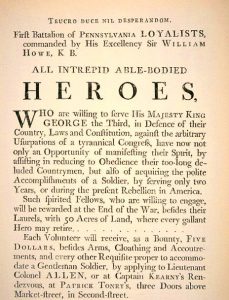

American Revolution (1775-1783)

Patriots and Tories

Within days of the battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, the first military engagements of the Revolutionary War, a formal protest against the government of England was circulated around New York. The signers were called “associators” and instantly became targets for possible reprisal. The Graham brothers – Augustine, Lewis, Morris, and Charles – were rich landowners originally from Morrisania Manor in Westchester County who had inherited land from their father, James Graham, in the Little Nine Partners Patent. They all signed, and all served in the war as officers, as befitted their class (see "People" page for more about the Grahams).

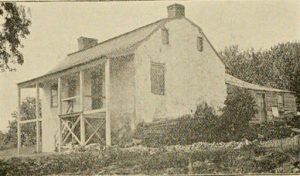

Lewis and Morris took leading roles in the colonial government. Lewis, who was still living in Morrisania but later fled for the safety of Pine Plains after the British invaded his home, was elected to the first Provincial Congress of the Colony of New York from Westchester County on May 8, 1775. He served at the second Provincial Congress (1775), was on a committee to detect conspiracies (1776) and served as a Judge of the Court of Admiralty (1778). Morris, who had built a stone house which still stands on Route 82 about a mile south of Pine Plains (see inset), represented Dutchess County in the first Provincial Congress.

When the Continental Congress ordered two regiments into service in Dutchess County in July of 1776, Morris Graham became a colonel of the second regiment. There is a tradition that the flat land at the foot of Stissing Mountain was the drill ground for Morris Graham and his regiment. It is also said that Morris used his own money to maintain his command and keep it in the field. It is believed that Morris was a close friend of George Washington and they would meet at the Beekman Arms in Rhinebeck to plan strategy. It is possible that George Washington even visited Morris here at his home in Pine Plains.

Lewis attained the rank of colonel, while Augustine became a lieutenant and Charles a captain.

Not all of Pine Plains was for the patriot cause. There is a story about a Tory (another term for Loyalist), Dr. Jonathan Lewis, who operated a store at the former trading post on the outskirts of town (the Dibblee-Booth House - see "The Hamlets" page for more information on the house and a drawing). He fled to Nova Scotia (a popular refuge for Tories) with his family at the start of the Revolution, then later returned to Pine Plains. However, he was treated with such scorn by the locals that he hung himself from the garret of the old store.

Mr. Hubbell and his cannon

Nestled between Winchell Mountain and Stissing Mountain, with no major highways or waterways for easy access, the area that is the town of Pine Plains today was an isolated backwater at the time of the Revolution. However, a pass near Mount Ross provided a possible means for Tories from Clinton in the Nine Partners Patent to invade the area with the intent of gaining access to storehouses in nearby Connecticut to the east.

Around 1760, a man known to us only as Hubbell arrived in this vicinity from Massachusetts, bringing with him a six-pound iron cannon on a boat sled (for transport over the snow-covered terrain). He proceeded to build a cabin on the north side of Little Stissing Mountain, near the spring at the watering trough where the road to Mount Ross is today. This cannon later came in handy for fighting off the Tories. In fact, Hubbell and his cannon are credited with single-handedly defending the frontier in several clashes with the enemy... at least, so goes the tradition. Yet remote Pine Plains would remain a secluded region for the duration of the war, and for many years after. Today, Hubbell’s name is given to the spring.

Cannons were a vital means of ammunition for the colonists. Iron as a commodity, mined in the hills of western Massachusetts and Connecticut and eastern New York, was so important to the war effort that it is possible we would not have won the Revolution without it. The furnaces of the iron foundries, such as the one in nearby Ancram, were kept hot, producing shot and cannonballs. It is said that Harris Scythe Works (under original proprietor Joseph Harris at his Andrus Rowe Corners shop in what was at that time Amenia) produced bayonets for the Continental Army.

The historical society has in its collection a “swivel gun” cannon, so-called because it was meant to be mounted on a swivel where it could be pointed in any direction. Due to the small caliber and short range of these cannons, they were not meant to inflict maximum damage but because of their portability were particularly useful on sailing ships. However, swivel cannons also had peacetime uses, such as for signaling and firing salutes, and could also be used in whaling. Our cannon, which dates from before the Revolution, was found among a rock pile in a field in the Federal Square historic district of Amenia and donated to the Society.

Part of this is taken from an article written by Pine Plains Historian Bernice Grant for “Arsenal of the Revolution” published by the Lakeville Journal, 1976.

War pensions

In 1776, the Continental Congress passed the country’s first pension law. In 1832, Congress enacted its most sweeping pension law to date, which, beginning as of March 4, 1831, allowed for full pay for life for all officers and enlisted men who had served at least 2 years in the Revolutionary War, and those who had served less than 2 years but at least 6 months were granted something less than full pay. The benefit was not dependent on financial need or disability and widows and orphans could collect any unpaid benefits due the veteran at the time of his death. In 1836, further legislation was passed which allowed a widow to claim her husband’s pension if they were married during his term of active service in the Revolution, for as long as she remained unmarried. But to claim a benefit was not an easy task. Proof of service and marriage were required, and documentation was not always available.

In 1842, 84-year old Mary Ingalls, whose Revolutionary War veteran husband Elihu Ingalls had died in 1823, applied (belatedly) for his pension under the pension legislation of 1836. Lieutenant Elihu Ingalls had served under Colonel Morris Graham of Pine Plains. Unfortunately, a fire had destroyed the papers Elihu had kept of his service. One can sympathize with the elderly widow, who now had to remember dates and details of her husband’s service and of their marriage, and find veterans still living who had served with him, or anyone who knew them, to corroborate her claim. In all, eight such witnesses submitted sworn testimony on her behalf, but it took two years before her application for the pension was finally approved.

Mary was to be paid $1444.30 in arrears from March 1831 – March 1844, then a semi-annual allowance of $55.55 from March 1844 to September 1844. Unfortunately, she had died in 1843. In her will, she left everything including her anticipated pension to her widowed daughter-in-law, Hannah Ingalls.

Sources and Suggested Further Reading:

History of the Little Nine Partners, by Isaac Huntting, Chas. Walsh & Co., Amenia, NY, 1897

The research on Mary Ingalls' pension application was donated to the Society by her descendant Susan Droege.

National Archives: "Using Revolutionary War Pension Files..."

"The Wars of the American Revolution"

The New York State Library: "The American Revolution"

Wikipedia: "Swivel gun"

War of 1812 (1812-1815) - American Revolution Part 2

The War of 1812 was fought mostly on the high seas, the St. Lawrence River, and the Great Lakes, so New Yorkers living in the Hudson Valley tend to dismiss it. Yet, we know that our Pine Plains school benefactor, Seymour Smith (see "Seymour Smith Academy" page), raised a company of volunteers for a year’s service and was stationed on Staten Island, so that tells us that other Pine Plains residents probably fought in this war as well. The only other Pine Plains residents we know who served in this war were Alfred Brush, William T. Woodridge, and the Rev. John Reynolds; Reynolds before he lived here.

So, what was this war all about, and how did it end? What did the United States hope to gain?

The War of 1812 has sometimes been referred to as the American Revolution Part 2. Why? Well, for one thing, it involved the same players as the American Revolution, the United States and Great Britain, and came about only a short time later. And even though the United States had won its independence from Great Britain, there were unresolved issues, particularly with shipping and trade. Yet, the United States was in a vulnerable position, having no national army or navy with which to defend itself, so for many years it was forced to just turn a blind eye to these problems.

Then starting in 1803 came the Napoleonic Wars between Great Britain and France, in which the United States attempted to stay neutral. However, both countries accused American ships of running goods for the other side and would arbitrarily stop them on the high seas to inspect their cargo holds, sometimes with violent results. The situation was made worse by the British policy of impressment, whereby British ships would board American ships to capture U.S. sailors to serve in the British navy. Although outlawed by the treaty that had ended the American Revolution, the British had continued this practice. Many Americans felt that the sovereignty of their new nation was being challenged, while others were looking for an opportunity to expand U.S. territory into Canada. Either way, the calls for war were growing louder, and war with Great Britain was finally declared in June 1812.

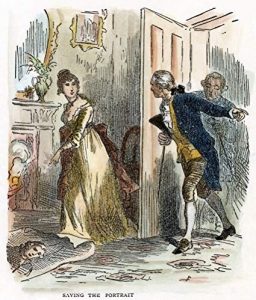

This is the war that gave us Oliver Hazard Perry uttering, “We have met the enemy, and they are ours” during the Battle of Lake Erie, a major victory for the Americans. It gave us the Star-Spangled Banner, which would become our national anthem. It gave us Uncle Sam, a real person who later became a national mascot. It is the war where the British burned down our nation’s capital, with First Lady Dolley Madison famously rescuing a portrait of George Washington from the burning White House. It is the war which made Andrew Jackson the hero of the Battle of New Orleans (which was actually fought after the treaty to end the war had been signed in 1814). These are some of the things the War of 1812 is remembered most for, because, although the United States won the war, it resolved little, and there were no geographic changes.

Still, the United States gained new confidence and proved that it was a military power to be reckoned with. What is more, it established a peace with Great Britain and our neighbor to the north that has lasted over two hundred years.

Source and Suggested Further Reading:

The Expanding Republic and the War of 1812: "The Second War for American Independence"

Civil War (1861-1865)

"Old Steady"

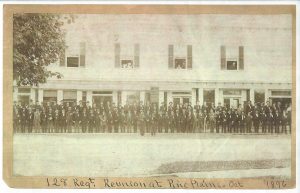

The 128th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment was a Civil War regiment of volunteers from Dutchess and Columbia Counties, including Pine Plains. It was mustered into service on September 4, 1862 from the fairgrounds in Hudson, New York under the command of Colonel David S. Cowles.

In early 1863, the regiment was sent down to New Orleans where their mission was to open up the Mississippi River to the Union. They played a major role in the Siege of Port Hudson, a Union victory but one where the 128th lost many men including their Colonel Cowles. It was after this engagement that the regiment earned the nickname “Old Steady”.

Other campaigns they participated in were the Red River Campaign and the Shenandoah Valley Campaign where they fought in the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, a Confederate victory. After this loss, many of the men of the 128th were sent to Salisbury Prison in North Carolina where they remained until release in February 1865. The regiment was mustered out July 12, 1865.

During its service the regiment lost by death, killed in action, 2 officers and 41 enlisted men; of wounds received in action, 20 enlisted men; of disease and other causes, 3 officers and 203 enlisted men. Total lost: 5 officers and 264 enlisted men for a combined total of 269.

Charles Ketterer, a German immigrant (one in four Union soldiers were immigrants) who was later the proprietor of the Ketterer Hotel in Pine Plains (see "People" page), signed up in 1862 and served in Company C of the 128th Regiment. Private Ketterer fought in both the Red River and Shenandoah Valley Campaigns, and liked to later brag that he came through the war without a single scratch. He learned the barber trade while in the war, and after the war set up the first barber shop in Pine Plains.

"The Dutchess County Regiment"

The other Civil War regiment that was recruited from Dutchess County was the 150th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, nicknamed "The Dutchess County Regiment". Joseph Near (1842-1863) was just a 20 year old country boy from Pine Plains when he volunteered with the 150th in October of 1862 for a three year hitch. He was in Company D, which was recruited mainly from the towns of Hyde Park, Pine Plains, North East, Poughkeepsie and Rhinebeck. We can imagine that he was excited to be going off to war, as young men often are, and that his parents were worried for his safety and maybe even begged him not to go. And like so many others before and after him, Private Near never saw home again. After participating in the Battle of Gettysburg, Near joined his regiment's long march to Virginia in pursuit of stragglers from Lee's retreating army. Unfortunately, the regiment camped on the north side of the Rappahannock River, which was lacking in fresh springs and in the heat of summer provided the ideal conditions for malaria, typhoid fever, dysentery, and other kindred diseases. Private Near fell victim to typhoid fever and died at Fairfax Seminary Hospital, near Alexandria, Virginia.

A Civil War soldier's chances of not surviving the war were about one in four. Disease was the biggest killer of the war; among the Federal dead, roughly three out of five died of disease, many diseases caused by the horrid filth found right in the army camp itself. Feared and often fatal, typhoid fever was one of the most terrible epidemic diseases in the 1800s. During the Civil War, of the 75,418 typhoid cases among white Union soldiers, 36% died.

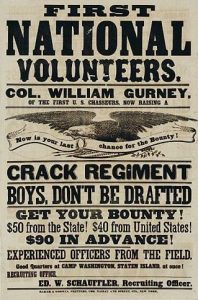

The Draft

When the Civil War draft lotteries began in 1863, it was the first concerted effort by the federal government to draft men into the armed services in this country’s history, although its real intent was to increase enlistments by acting as a threat and portraying volunteerism as the “honorable” route, an effort which largely failed. The draft was only imposed when district quotas were not met, and money was often raised by communities as bounties to be paid to volunteers to satisfy their quota. Congress anticipated public indignation against the draft and therefore instituted several means of evasion for a draft-aged man. Commutation was one method, which was the payment of a fee of $300, good for that draft lottery only. Another method was by hiring a substitute, which also cost $300 until commutation was abolished and then its price skyrocketed; this exempted the man whose name was called for the duration of the war, and there were substitute brokers for those having difficulties finding one.

Public opinion on the draft appears to have been divided. Some favored it, viewing it as a patriotic duty and necessary for the Union to win the war. Others were okay with the draft on principal but did not feel comfortable with the use of federal power or martial law to enforce it, or they felt that the ability of the rich to buy their way out of serving discriminated against the poor, making the war a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight”. A group of wealthy New York Democratic businessmen even tried to have the draft declared unconstitutional. Organizations sometimes raised funds to help pay the commutation fees for its members. There were draft riots, most notably in New York City. Overall, the draft was unpopular and there was more of a stigma on being a draftee than on using one of the legal means of draft evasion!

The government learned its lesson from the Civil War draft and future drafts did not allow commutation or hiring substitutes.

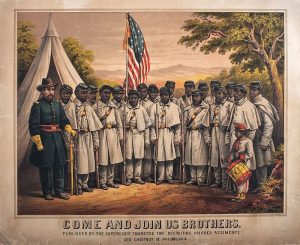

Black troops

The history of the service of African Americans in American wars right up through the mid-20th century is complex. Whether slave or free, from not being allowed to serve, or to fight, to being segregated from their fellow brothers-in-arms, it varied over time and place.

At the time of the American Revolution, slavery was still legal in all 13 colonies. There were black soldiers in the Continental Army, but at first these were freemen or slaves serving for their masters. Washington initially resisted allowing slaves to serve in the Army. The British saw an opportunity: the offer of freedom to slaves who ran away and joined the British forces. Eventually, Washington had little choice but to do the same for slaves on the American side. The Navy had fewer restrictions than the Army on the recruitment of African Americans because lack of manpower in the Navy was an ongoing issue. Blacks also served in northern state militias, but were forbidden to serve in southern militias because Southerners feared arming slaves.

When the Civil War started, abolitionists including Frederick Douglass argued for the enlistment of black soldiers. However, President Lincoln was forced to appease the border states to keep them from going over to the Confederate side, and he feared that if he allowed blacks to serve he would lose these critically important states. So blacks, whether they were free or escaped slaves, were initially not allowed to serve in the Union Army.

As the war dragged on, President Lincoln changed his mind, and the Second Confiscation and Militia Act of 1862 allowed him to receive persons of African descent into the military service, but not as combatants. After the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the Bureau of Colored Troops was established with the purpose of facilitating the recruitment of blacks (as well as other people of color including Native Americans) for combat. Horace Buckner, a Kentucky slave who settled in Pine Plains after the war (see "People" page), served with the 6th U.S. Colored Calvary, organized in Kentucky in late 1864. To speed up recruiting in the border states including Kentucky, the War Department issued General Order No. 329 that any citizen who offered his or her slave for enlistment into the military service would be compensated with $300, and emancipation for the slave was included in the deal. This is most likely how Horace Buckner came to be enlisted with the United States Colored Troops and obtained his freedom.

Sources and Suggested Further Reading:

Wikipedia: "128th New York Volunteer Infantry"

Commemorative Biographical Record of the Counties of Dutchess and Putnam, Vol 2

New York State Military Museum: "150th Infantry Regiment Civil War"

The Dutchess County Regiment: "Battle of Gettysburg" by Joseph H. Cogswell

Civil War Rx: "Typhoid Fever", by Alfred J. Bollet, M.D.

Civil War Medical Care, Battle Wounds, and Disease

Letters from Charley Goodyear: "Fairfax Seminary Hospital"

United States History: "The Draft in the Civil War"

War History Online: "The Drafts - Building the Armies of the American Civil War"

History.com: "Black Civil War Soldiers"

Wikipedia: "United States Colored Troops"

Constitutional Rights Foundation: "Black Troops in Union Blue"

Spanish-American War (April-August 1898) - "A Splendid Little War"

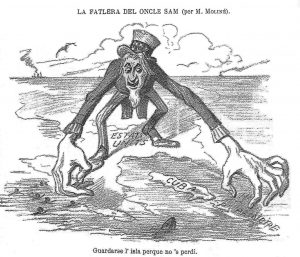

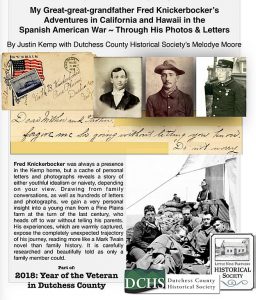

Two men from Pine Plains, Fred Bostwick and Fred Knickerbocker (1876-1956), fought in the Spanish-American War, and yet most Americans today have very little knowledge of this long-forgotten war, which was America's first war fought overseas. They may have a vague recollection of learning about Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and the Battle of San Juan Hill, or something about the sinking of a battleship, the USS Maine. But other than that, there is little understanding of the details or significance of this war. However, like an earlier American war that is similarly forgotten -- the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), in which the United States acquired a huge chunk of the North American continent, from Colorado and Texas west to the Pacific Ocean -- the Spanish-American War was important in expanding United States dominance in the Western Hemisphere. The Spanish-American War ended hundreds of years of Spanish colonial rule in the Americas and added several new territories to the United States in Latin America and the western Pacific.

Tensions between the United States and Spain had been brewing for some time. Cuba was involved in a struggle for independence from Spain, and Americans sympathized with Cuba from a humanitarian standpoint. Also, American trade with Cuba, estimated to be worth $100 million annually, was being impacted by the ongoing war between Spain and the Cuban insurgents. When the USS Maine, sent to Cuba to protect American interests there, exploded in Havana harbor in February 1898, killing 260 of her crew, tensions escalated and the battle cry, “Remember the Maine!”, was splashed on the front pages of newspapers across America. American intervention in Cuba’s fight for independence seemed eminent, and Congress passed the Mobilization Act to raise an army of 125,000 volunteers; there would be no draft in this war. On April 25, 1898, the United States declared war on Spain. By July, Secretary of State John Hay was calling it, "a splendid little war".

Tensions between the United States and Spain had been brewing for some time. Cuba was involved in a struggle for independence from Spain, and Americans sympathized with Cuba from a humanitarian standpoint. Also, American trade with Cuba, estimated to be worth $100 million annually, was being impacted by the ongoing war between Spain and the Cuban insurgents. When the USS Maine, sent to Cuba to protect American interests there, exploded in Havana harbor in February 1898, killing 260 of her crew, tensions escalated and the battle cry, “Remember the Maine!”, was splashed on the front pages of newspapers across America. American intervention in Cuba’s fight for independence seemed eminent, and Congress passed the Mobilization Act to raise an army of 125,000 volunteers; there would be no draft in this war. On April 25, 1898, the United States declared war on Spain. By July, Secretary of State John Hay was calling it, "a splendid little war".

Soldiers, sailors, and marines were deployed to Cuba and the Philippines where most of the fighting took place. But Spain was outmatched by the sea power of the United States, and the fighting was over by August, before most of the men had reached their destination. The Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898, established the independence of Cuba, ceded Puerto Rico and Guam to the United States, and allowed the United States to purchase the Philippine Islands from Spain for $20 million.

The United States lost 3,000 lives in the war, of whom 90% died from infectious diseases.

Sources and Suggested Further Reading:

Read more about Fred Knickerbocker on the Dutchess County Historical Society website: Fred Knickerbocker's "Great Adventure"; Getting to Know My Great-Great Grandfather Fred

Library of Congress: "The Spanish-American War"

World War I (U.S. 1917-1918)

At the time America entered World War I in 1917, the country was still largely rural and small town. Many of the young recruits from Pine Plains were farmers who had never been far from home. One can imagine that the prospect of going overseas for the first time filled many of them with romantic notions.

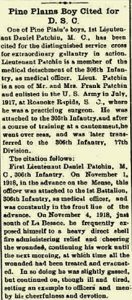

Over 70 men from Pine Plains were drafted or enlisted in the armed services. Not all went overseas; some were stationed their entire tour of duty in stateside camps. Two died during the war. We know of one Purple Heart awarded (Raymond Harris) and one Distinguished Service Cross for Bravery in Action (see inset) - Daniel Patchin (1889-1949), who later became a physician in Buffalo, New York.

Although we know very little about the men from Pine Plains who served in the Great War at the time of their service, their draft registration cards do tell us some things. For example, we know their occupations, which were surprisingly varied for a rural community: farmer, worker for GE in Schenectady, dentist, student, milker at Briarcliff Farms, mason, machinist, painter, well-driller, veterinarian, driver for Hudson River State Hospital, store clerk, and "commission man", to name a few.

The draft registration cards also tell us where the registrant was born, and Pine Plains had a few young draftees who were citizens of other countries, namely Italy and Holland. Dutchman Antoon DeVries worked at Briarcliff Farms, which is not surprising to anyone who knows anything about that large operation: Briarcliff Farms employed milkers from Holland because they had a reputation as the best milkers in the world.

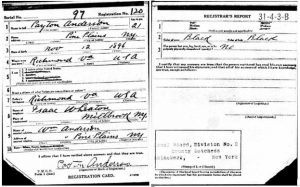

The form also had a field for the race of the applicant, but if the applicant was of "African descent" they were required to clip off the bottom left corner of the form. We know of only one black man from Pine Plains who served in WWI: Payton Anderson (1896-1958). Private Anderson never went overseas. Instead he was stationed at Camp Humphreys in Virginia for his entire service, from October – December 1918. We don’t know any specifics about his service there, but we do know that the heavy labor of the construction of this camp over an 11-month period, beginning in January of 1918, was performed by segregated African American troops.

Several brothers enlisted together, including the four Harris brothers: Clifford, Leigh, Paul, and Raymond. All four survived the war, and Raymond Harris earned a Purple Heart.

On the home front

In addition to those who served in the armed forces here and abroad, many contributed in other ways here at home. One of these was through a volunteer civil defense militia called the Home Defense Corps, which was composed mostly of men 45 to 64 years old who for various reasons were unable to enlist in the army or navy.

This photo (see inset) of Memorial Hall in Pine Plains was taken on May 20, 1917 with Company G, 1st Infantry, New York Guard lined up in front. The New York Guard was created after the National Guard was mobilized and sent overseas. In January of 1918 Memorial Hall was made an armory of the NY Guard.

This photo (see inset) of Memorial Hall in Pine Plains was taken on May 20, 1917 with Company G, 1st Infantry, New York Guard lined up in front. The New York Guard was created after the National Guard was mobilized and sent overseas. In January of 1918 Memorial Hall was made an armory of the NY Guard.

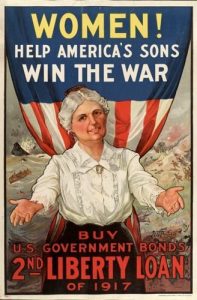

In July of 1918, Pine Plains received a W.S.S. service flag for oversubscribing to the War Savings Stamp Drive. Pine Plains, in fact, was the first town in Dutchess County to exceed its quota in the drive, which was $26,000. Pine Plains subscribed $28,550. Samuel Deuel (see "People" page) was the chairman of the drive committee and received the flag which was flown at the Stissing National Bank. War Savings Stamps were issued by the Treasury Department and used to fund participation in the war. These stamps were aimed at everyday citizens rather than businesses. Pine Plains was also on the Liberty Loan Honor Roll for war bond subscriptions several thousand dollars over its allotment of $41,900.

Welcoming the boys home

On Sept. 12, 1919, ten months after the end of the war, Pine Plains held a big celebration to welcome the boys home, arranged by Company G of the New York Guard with an evening banquet organized by Mrs. W.J. Bowman. There was a concert given by the Rhinebeck Band from 2-4 pm, who then led a parade at 4:00 with the returning veterans as well as veterans of the Civil War, Company G New York Guard, women of the Red Cross, Boy Scouts, school children, and fraternal organizations.

The parade halted at the high school, where Dutchess County service medals were presented to the boys by Supervisor Vernon J. Rockefeller and the principal address was given by Judge Charles S. Wilber, President of the 128th Regimental Association and a Civil War veteran (see "People" page). This was followed by a supper beginning at 6 pm at Memorial Hall attended by the boys, their wives and parents, and other honored guests, where an address was given by Assemblyman J. Griswold Webb, an early supporter of veterans’ rights.

Sources and Suggested Further Reading:

The Pine Plains Register

The Columbia Republican, Tuesday September 16, 1919

The National Museum of American History: "The Draft During WWI"

Westchester Magazine: "How WWI Was Fought on the Hudson Valley Front"

U.S. Army Center of Military History: "Camp Humphreys"

Smithsonian's Postal Museum: "African American Troops in WWI"

Dutchess County Historical Society: "Year of the Veteran - Pine Plains" Read about Corporal Lester Whitney's remarkable map and journal, see a spreadsheet of the Pine Plains men who served, read local newspaper clippings, and read the tragic story of expert gunner Henry Bathrick.