When people think about the institution of chattel slavery that existed in the United States before the Civil War, the first thing that usually comes to mind is an image of slaves working in the fields on large plantations in the South. However, slavery was very much a part of northern life as well, and life for a northern slave could be just as brutal. By 1790, New York was the largest slave-holding state north of the Mason-Dixon line, a distinction due in large part to the number of slaves in New York City. Although it was abolished in New York in 1827, gradual manumission laws kept some slaves bound to their former masters as indentured servants until 1848, as explained here:

https://omeka.hrvh.org/exhibits/show/missing-chapter/manumission-act-of-1799

There were some important differences between slavery in the North and South. Northern farms were generally smaller, and since the growing season here was shorter and slaves could only work in the fields part of the year, the rest of the time they would clear land (chopped wood was also needed for the making of charcoal), run mills, or work at other trades, and it was a common practice for middle-class tradesmen or shop-keepers to own one or two slaves. In the Hudson Valley, slaves also helped with the patent surveys. The result was that most slaves tended to live singly or in small groups, unlike on the large southern plantations. Most slaves in the North had more freedom of movement than their southern counterparts. It is also important to note that, due to gradual manumission laws in New York, there were three degrees of freedom: slave, indentured servant, and free, and all three could co-exist in one household.

There isn't a lot of information about slavery in Pine Plains, but it appears that it was like other small rural northern towns. However, due to the number of mills here it seems reasonable to assume that slaves were used to run them.

Perhaps the earliest reference to slavery in the area is of a mixed-race slave who was owned by Joseph Harris, the blacksmith at Andrus Rowe Corners just north of the current hamlet of Shekomeko in the town of North East, named for the Mahican village that had been located in Pine Plains. It was this skilled slave whose name is lost to history who taught Joseph Harris the trade of scythe-making. Joseph's nephew John Harris worked alongside Joseph and his slave in this shop, and around 1783 John settled in what became Pine Plains where he set up his own Harris Scythe Works at Hammertown.

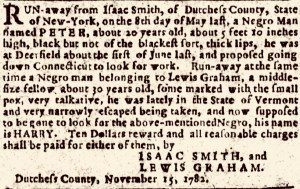

This runaway slave notice from 1782 (see inset), which pertains to Pine Plains, is fairly typical of the period. Lewis Graham (of the Graham-Brush House) was one of over five children born to James Graham, son of Little Nine partner Augustine Graham who had been Surveyor General of the Province of New York. Patriots in the Revolution, the Graham children were also slave owners. They had inherited several of the patent lots from their father, eventually settling here for a few years and becoming active in local politics. Although Lewis Graham lived most of his life on the family estate in Morrisania (the South Bronx today), at the time of this notice he was hiding out in Pine Plains in the house now named for him, a refugee from the war after the British takeover of Morrisania. Isaac Smith, Esq. (ca. 1731-1821) was a lawyer who lived on the south end of Pine Plains. The fate of the runaways Peter and Harry is unknown; although there were no fugitive slave laws yet on the books, newspaper ads like the one above testify that the pursuit of escaped slaves in the North was every bit as relentless as it was in the South.

Isaac Huntting calls our attention to the following bill of sale, dated April 1, 1784, from Augustine Graham (brother of Lewis), who apparently was having financial difficulties, to their brother Morris, which says in part:

"A bill of sale given by Augustine Graham to Morris Graham for the whole of his movable estate, viz.: his negro man Philip, and negro wench Salina, and her four children Joe, Robin, Jonathan, and Moses, with three old cows and three heifers... and three old mares, wagon, plow, sleighs, harrows, and all other his farming utensils."

The 1790 federal census was the first census for the new country and gives us our first real look at how many slaves some early Pine Plains residents had. The census only recorded the name of the head of household, and then counted the number of people in the household in each of the following categories: free white males of 16 and upwards; free white males under 16 years; free white females; all other free persons; and slaves.

At the time of the 1790 census, Augustine Graham, now the only remaining Graham still living in Pine Plains, had a household of twelve, of which six were slaves. One is left to wonder if he acquired more slaves after the above bill of sale, or if the sale never went through.

(see "People" page for more on the Grahams)

The 1800 census shows the household of Pine Plains shop owner Ebenezer Dibblee with 6 slaves; by 1820 this number had decreased to two male slaves, which we know because the 1820 census asked for more information than previous censuses, including the sex and ages of slaves. The decrease in the number of slaves in New York households often seen around this time was common as slavery was winding down, due to gradual manumission laws.

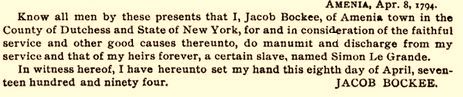

We know quite a bit about one early Pine Plains resident who was a slave owner: Jacob Bockee (1757-1819), the man who in 1816 sold the piece of land to the Quakers in Bethel for their mission house. As a young man of eighteen, Jacob, originally from Amenia but later settling in Pine Plains, lost his parents and inherited the family farm which was located near the present hamlet of Shekomeko. When he went off to fight in the Revolution, he left instructions for the twelve slaves in the household to "get their living off the farm", presumably so that they would have a means of survival during the war.

By the 1790s he was freeing some of his slaves; there is a record of his freeing one Simon Le Grande in 1794, as follows:

As a member of the New York State Assembly from 1795-1797, he called for the abolition of slavery in New York, but a law for gradual abolition did not pass until 1799. In 1815 he settled on the former John Tice Smith farm in Bethel, and that same year he freed his slave Clara and her two-year old son, Charles, presumably having waited until Clara was old enough to take care of herself as the law required. It may be of interest to know, and it certainly gives additional insight into Jacob's character, that he also was involved with a temperance society where any violation was cause for the member to forfeit his right arm. Jacob's son Abraham became a U.S. Congressman.

As a member of the New York State Assembly from 1795-1797, he called for the abolition of slavery in New York, but a law for gradual abolition did not pass until 1799. In 1815 he settled on the former John Tice Smith farm in Bethel, and that same year he freed his slave Clara and her two-year old son, Charles, presumably having waited until Clara was old enough to take care of herself as the law required. It may be of interest to know, and it certainly gives additional insight into Jacob's character, that he also was involved with a temperance society where any violation was cause for the member to forfeit his right arm. Jacob's son Abraham became a U.S. Congressman.

The following entry is from the town record books (remember that Pine Plains was still part of North East at this time). Apparently, Driss was about to be freed, and a determination had to be made that he was able to take care of himself (as required by law) and would therefore not become dependent on the poor house.

We, the subscribers, Overseers of the Poor of the Town of Northeast, in the County Duchess, do certify that Driss, a slave of Nicholas row, of said Town of Northeast, appears to be under the age of fifty years, and of sufficient ability to provide for himself. Northeast Town, Oct. 26, 1813 , Jeptha Wilbur, Philo M. Winchell, Overseers of Poor.

As with any other property, wills were often used to bequeath one's slaves to someone. They were also used to give slaves their freedom. Here is an excerpt of the will of Benjamin Knickerbocker, Sr. (1728-1805) of Pine Plains (then part of North East), showing an example of both.

Rev. William N. Sayre, the pastor at the Union Meeting House and then the Presbyterian church, was a member of the Dutchess County Anti-Slavery Society and is thought to have been active in an Underground Railroad in Pine Plains, but there is no evidence to support this and we are not aware of any Underground Railroad stations that existed in Pine Plains.

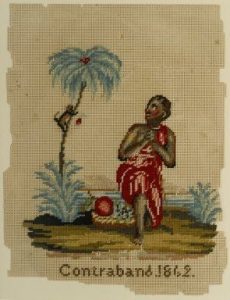

The needlework pictured here is on loan to the Brooklyn Museum. When the museum acquired it in 2006 they contacted the historical society because they were hoping we could give them some information on the original owner, Ruhamer Bird (whom they presumed had made it), and they mistakenly thought she was from Pine Plains. In fact, Ruhamer Bird (1830-1910) was a Stanford socialite who lived in the beautiful Greek Revival mansion that still stands on Hunns Lake Road near Carpenter Hill Road, just south of Pine Plains. While she very well could have made this, the evidence was just not conclusive enough and the museum has attributed it to "unknown". Here is what they say about the piece on their website:

An abolitionist made this small, unfinished embroidery during the Civil War (1861–65), the year before the Emancipation Proclamation made slavery illegal in the rebellious Southern states. The composition is most likely derived from a political print of the era. At the outset of the Civil War, the North’s goal was not the abolition of slavery, but rather the preservation of the Union. It was a law in the North that runaway slaves, called “contraband,” were to be returned, although some Northern generals refused to do so. At first Lincoln himself wavered on this issue, but the fate of runaways became a political issue after the Union army occupied the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina in November 1861 and discovered ten thousand abandoned slaves. An outpouring of support for these abandoned slaves and other slaves who had escaped persuaded Lincoln to add emancipation as a goal of the Civil War and led directly to his Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863.

Sources:

History of the Little Nine Partners, by Isaac Huntting, Chas. Walsh & Co., Amenia, NY, 1897.

The Bockée Family, by Martha Bockée Flint

The Pine Plains Register

Suggested Further Reading:

"Ante-Bellum Dutchess County's Struggle Against Slavery", by Susan J. Crane, Yearbook of the Dutchess County Historical Society, 1980, Volume 65.

New York Slavery Records Index

Slavery and Freedom in the Hudson Valley, by Michael E. Groth (book preview)

Slavery in the Northern United States (great maps)