At one time, Pine Plains was a very busy place, with 18 trains going in and out of the town daily. The railroads transformed what had been an isolated farming community. In the days before cars and trucks, it was the railroads that brought businesses and people, some of them tourists, to Pine Plains. They made it possible for country folk to commute daily to jobs in the city. They transported bulk goods. Pine Plains on the threshold of the 20th century was a very different place than it had been 40 years before, all because of the railroads. And although they are long gone, the romance of the railroads and trains lives on.

[This page will attempt to give an introductory, high-level overview of the development of the railroads in Pine Plains, since there is already so much information available on this subject which goes into far greater depth and does it very well. See sources and suggested further reading at bottom.]

Before the railroads

What was it like before the railroads came? Well, for long distance passenger travel on land there was the stagecoach. People tend to associate stagecoaches mostly with the American West, but they were how people got around all over before railroads. In 1830, the first stagecoach route, with a team of four horses, was established in Pine Plains, carrying both mail and passengers twice a week from Pine Plains to Poughkeepsie, returning the next day. This was along what is State Route 82 and U.S. Route 44 today. Later, it ran three times a week. It was slow (the average speed 5 miles per hour), the roads were not very good, and space was limited. Goods were transported by horse and wagon, which was even slower. Roads gradually improved after the first macadam road in the United States was built in 1823.

What was it like before the railroads came? Well, for long distance passenger travel on land there was the stagecoach. People tend to associate stagecoaches mostly with the American West, but they were how people got around all over before railroads. In 1830, the first stagecoach route, with a team of four horses, was established in Pine Plains, carrying both mail and passengers twice a week from Pine Plains to Poughkeepsie, returning the next day. This was along what is State Route 82 and U.S. Route 44 today. Later, it ran three times a week. It was slow (the average speed 5 miles per hour), the roads were not very good, and space was limited. Goods were transported by horse and wagon, which was even slower. Roads gradually improved after the first macadam road in the United States was built in 1823.

Waterways were also used to transport people and goods before railroads. Packet boats which operated by sail, and then steamboats after 1807, plied the Hudson River between New York City and Albany. For communities inland such as Pine Plains, access to waterway transport meant first making the journey over land to the river.

The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 had a profound impact on the migration of peoples west and on commerce in early America, even for far away communities like Pine Plains. The canal gradually brought about a major changeover in New York farming from the production of wheat to dairy. Prior to the Erie Canal, most farmers in New York, including Pine Plains, grew wheat. But once the Erie Canal opened up, these farmers found themselves in competition with western wheat markets and many switched over to dairy farming as a result. New York soon became the heart of America's dairy industry (until Wisconsin supplanted it in the early 20th century).

Then the railroad came along. Land would have to be acquired and financial backers found. Meanwhile, the safety of rail travel to both body and soul was questioned: some physicians were concerned about its effects on the human body, while some clergymen saw railroads as something akin to the devil.

Getting the land

All forms of public transportation require the acquisition of land to support them. If homes and farms were in the proposed path of the road, canal, or train tracks, most of the time the landowner could be swayed to donate or sell his land for the "greater public good". In cases where the landowner could not be convinced to give up his land, the state had the legal right to take it without his consent, as long as the landowner received "just compensation". This is called eminent domain, and the power to exercise it is granted to the federal government in the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and to New York in the state constitution. It has been challenged in court multiple times.

In many cases, however, instead of buying the land outright, the railroads acquired a right-of-way to use the land.

[This page does not address the massive federal and state land grants to railroads with the purpose of building the transcontinental railroad and settling the American West. For more on that, go here: https://www.endeavoradvisors.com/historical-research-and-development-of-the-transcontinental-railroad/]

The Long Distance Lines: connecting the Great Lakes to New York City

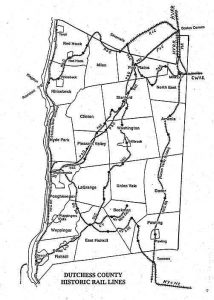

The first two railroads in Dutchess County were long-distance north-south lines that originated in New York City and terminated in Albany, making several stops as they traversed through the county. They were built to take advantage of the western trade from the Great Lakes and the Erie Canal. The New York & Harlem Railroad went from Manhattan to Albany through the Harlem Valley of eastern Dutchess County, and the Hudson River Railroad hugged the Hudson River shoreline from Manhattan to Albany. Both lines were completed by 1852.

Steamboat travel couldn't compete with the Hudson River RR. A trip by train from New York City to Poughkeepsie took 2½ hours. This was the final stop at the outset, and passengers would disembark and if going on to Albany would either take a steamboat, or in winter a stagecoach. The distance from Poughkeepsie to Albany was shorter than from New York to Poughkeepsie, yet it would take another 4½ hours by steamboat for this leg of the journey.

"Canal Fever"

There would be no "short lines" (that is, lines that originated and terminated within Dutchess County) for another two decades, even though there were proposals on the table.

Lack of funds was a factor. Railroads were partly financed by the local towns that would be serviced by them, and Dutchess County had been hit hard by the financial panics of 1837 and 1857. Also, the public was still gripped by "canal fever". In 1833, an attempt to construct a railroad from Poughkeepsie through Pine Plains to the Connecticut state line failed, followed by another failed attempt in 1836. Both failed because most people wanted a canal instead. The end result was that they got neither.

The railroads, at least in New York, had a couple of advantages over canals. For one thing, although trains could get snowed-in, railroads remained in service year-round, whereas canal transport was seasonal since the canals froze in the winter. Another advantage was that rail lines could go everywhere: eventually, most major cities and even small towns were serviced by a railroad.

Dutchess County was uniquely positioned to take advantage of east-west rail traffic. An intensive PR campaign was waged to convince people that investing in railroads was the right way to go. While politicking over routes led to further delay, more and more people began to support the idea of railroads over canals.

Industry boomed after the Civil War, ushering in a new Industrial Age and creating new opportunities for growth. Soon, railroad development in Dutchess County would take off, catching up to other areas of the state. The county would ultimately have so many miles of track that they reached each of its 20 townships at least once.

The Short Lines: connecting Pennsylvania to New England

The pressing demand for a quicker route from the eastern Pennsylvania anthracite coal fields to New England, which needed the coal for its manufacturing and heating, was the prime motivation behind building the east-west railroads in Dutchess County. We will focus here only on those railroads that went through the hamlet of Pine Plains.

The first east-west line to be incorporated, on April 23, 1866, was the Poughkeepsie & Eastern Railroad (P&E). This route ran from Poughkeepsie northeast to Pine Plains, then a short distance to Boston Corners in Columbia County before coming back down to State Line east of Millerton, where it made its connections with the Connecticut Western Railroad.

The second line was the Dutchess & Columbia Railroad (D&C), incorporated on Sept. 4, 1866. Its first president was Millbrook tycoon George H. Brown. Connecting to the Erie Railroad in Newburgh by ferry across the Hudson River (ferrying the railroad cars) from its western terminus at Dutchess Junction south of Beacon (Fishkill Landing at the time), this line traveled northeast to Pine Plains then east through the hamlet of Bethel on its way over to Millerton and the Connecticut state line, where it connected to the Connecticut Western Railroad.

There was a not-so-friendly competition between these two railroads to see who would finish first. Some investors asked to invest in one were already committed to the other. There was also the concern that one line would take away business from the other because they followed similar routes. In Pine Plains, exaggerated sales pitches were used to entice wary residents to buy into the P&E, such as, "at the end of ten years the village of Pine Plains will contain five thousand inhabitants" (the population was only around 1500 by the 1880s and is around 2500 today), and the prediction that farms in Pine Plains would increase 25% in value within three years of the railroad's completion.

The 58-mile long D&C would reach Pine Plains in 1869 and was completed first in 1871 at an estimated cost of $2,230,000. The 43-mile long P&E was completed in 1872 at a cost of $1,499,200. In the end, the two railroads would end up sharing some track: the P&E leased track from the D&C between Stissing Junction, south of Pine Plains, to Pine Plains, beginning at an annual rate of $10,000.

Financial failures and reorganizations

The history of the short lines in Dutchess County is a chronicle of financial failures and reorganizations, of which the following is a very brief summarization.

Before the D&C was even completed it was leased to the Boston, Hartford, & Erie Railroad. By 1874, foreclosure proceedings were begun and it was sold in 1876 and reorganized in 1877 as the Newburgh, Dutchess and Connecticut Railroad (ND&C), affectionately nicknamed "The Never Did and Couldn't". In those days, every Tuesday was cattle day, in which a cattle car was placed at the railroad stockyard and farmers from far and near drove cattle there to be shipped to New York.

As for the P&E, it had been estimated that annual revenue from the hauling of iron ore, its #1 source of income, from the Columbia County Iron Mining Co. and the Weed Iron Mine near Boston Corners, would be $87,000, followed by the hauling of milk at $58,000, and lastly by passenger service at $42,000. However, the receipts were far below these expectations, the total of all three being $86,000 in 1873 and steadily declining from there.

In the 1880s, a third short line railroad came into Pine Plains hamlet, the Poughkeepsie and Connecticut Railroad (P&C). It was built to connect the new railroad bridge in Poughkeepsie with New England. However, the bridge builders' original intent to buy the old P&E line on the Poughkeespie side to give them access to Millerton fell through when they found out the P&E line was not for sale! The 28-mile P&C line was therefore built parallel to the P&E, with a spur joining the leased "Huckleberry" line at Silvernails just north of Pine Plains in Columbia County.

In 1905, the New Haven Railroad purchased the ND&C and in 1907 it purchased the old P&E (now named the New York & Massachusetts Railroad). These were merged that same year into the Central New England Railroad (CNE), which operated under New Haven's control. In 1910, the CNE consolidated the P&E and P&C lines into one line. Some lines were discontinued during the consolidation process, such as the section to Millerton via the hamlet of Bethel, with that station closing in 1907.

The failure of these short lines in Dutchess County was the result of a combination of factors. Certainly, the competition of so many railroad lines for the same businesses played a part. There was also a decline in the availability of the raw materials the railroads were built to transport, as quarries and mines were depleted.

However, the failures here were mirrored in communities across the country. There was the "Long Depression", the economic downturn after the Financial Panic of 1873, which lasted until 1878/9. The collapse of the railroad financiers had actually been a major cause of the panic, and railway construction halted. Later, the improvement of roads and the development of the truck and the automobile, promoted as superior modes of transportation, made the railroads obsolete.

The abandonment of the CNE lines in Dutchess County was a gradual process. The last passenger trains out of Pine Plains were dispatched on Sept. 9, 1933. Freight service would continue to/from Pine Plains until 1937. The tracks were eventually pulled up and sold as scrap to Japan.

The impact of the railroads on Pine Plains

There is little doubt that the railroads, while ultimately not profitable, had a significant impact on life in Pine Plains. Employment opportunities increased as men and women were able to take the train into Poughkeepsie. Farms expanded: now that raw milk could be shipped by train, production had to increase to meet the demand, which meant farmers had to increase the size of their dairy herds. The huge Briarcliff Farms operation most likely would not have relocated from Briarcliff Manor to Pine Plains without the railroad (see "Briarcliff Farms and its Successors" page). The railroad also made the Pine Plains hamlet a viable location for Borden's Milk Company (see inset above).

Industries like apple drying and barrel making became more popular. Dried apples were used in a variety of recipes, and a way to have apples year-round in the days before refrigeration. Drying was also the best way to transport long distances. The dried apples would be packed in barrels for shipping by railroad; in fact, barrel-making was a big business once upon a time in Pine Plains. Evaporators (see inset) were once all over the Northeast. With the advent of refrigeration and refrigerated shipping, the need for drying became obsolete, and most of the evaporators eventually closed.

During the railroads' heyday, the hamlet of Pine Plains easily supported two drug stores, two large hotels (as well as several boarding houses), multiple dry goods merchants and general stores, a renowned boarding school, and several entertainment venues. Doctors and lawyers were in no short supply. The town even had two weekly newspapers for many years. While Pine Plains may not have quite lived up to those early P&E sales pitches, the fact of the matter is that the town, and particularly the Pine Plains hamlet, did see substantial growth and economic prosperity because of the railroads.

The railroads had been built mostly with immigrant labor, many from Ireland; they boarded here while working on the railroads and some stayed on after the work was completed. Also, as Lyndon A. Haight notes, these were family railroads, employing many local people who therefore paid taxes in Pine Plains.

When trucks replaced the railroads the transport methods changed again. Milk went from shipping in cans to bulk, and coal was now stored in silos where it could be sorted (see inset).

Although the days of these local railroads have long passed, they have left many fond memories with the few who are still living that remember them, and they continue to inspire new generations of railroad enthusiasts.

The future: rail trails

Turning old railroad beds into walking and biking trails is a trend throughout the country, and a great way to enjoy nature, get some exercise, and learn a little railroad history all at the same time.

There are currently no rail trails in Pine Plains, although they could become a reality some day. In the meantime, there are two rail trails in Dutchess County. The old Maybrook rail corridor running through the middle of Dutchess County from the Hopewell Depot to the Hudson River has been converted into a 13.4-mile trail, called the William R. Steinhaus Dutchess Rail Trail. At the river, the trail connects to the former railroad bridge which is now the Walkway Over the Hudson State Historic Park, and on the west side of the Hudson it connects to the Hudson Valley Rail Trail. In eastern Dutchess County, the abandoned portion of the New York and Harlem Railroad has been converted into the Harlem Valley Rail Trail, 10.7 miles of completed trail from Wassaic north to Millerton, and an additional 5 miles from Under Mountain Road in Ancram to Orphan Farm Road in Copake; the rest of the trail is in various stages of development.

Sources and Suggested Further Reading:

History of the Little Nine Partners, by Isaac Huntting, Chas. Walsh & Co., Amenia, NY, 1897

Pine Plains and the Railroads, by Lyndon A. Haight, a LNPHS publication, 1976

Associated of American Railroads: "Chronology of Railroading in America"

New York State Dept. of Transportation: "History of Railroads in New York"

Clinton Historical Society: "Dutchess County Railroads", by William P. McDermott

Rich's PedalPoint: "Retracing Abandoned Railroads in Dutchess County"

"The Lost Railroads of Pine Plains", a talk by Bernie Rudberg

"History of Dutchess County", edited by Frank Hasbrouck, published by S.A. Matthieu, Poughkeepsie, NY, 1909

"Upper Dutchess County Railroad History"

Parks and Trails New York: "Getting on Track: Working with Railroads to Build Trails in New York"

Railroads and Clearcuts: "Taking Back Our Land: A History of Land Grant Reform"

Lockport Union-Sun & Journal: "Canal Discovery: Eminent Domain"

"Railroad History: Who Constructed Railroads?"