This page is dedicated to Elizabeth Jordan Klare (1914-1995), a charter member of the Little Nine Partners Historical Society, who had always wanted to write a publication for the Society on the industries along the Shekomeko Creek.

The harnessing of water power goes back at least 2,000 years. When the surveyors for the Little Nine Partners Patent began their task in 1743, one of the things they looked for were streams that would make good mill sites. A good mill site would be next to a natural waterfall, where power could be increased by building dams.

A tributary of the Roeliff Jansen Kill, the Shekomeko Creek was named by early white settlers after the Mahican Indian village that existed in the current hamlet of Bethel. The name Shekomeko is sometimes translated as "place of eels", suggesting that at one time the creek may have had a sizeable American eel population. Today it has both wild brown and brook trout populations. The creek has its source on Carpenter Hill in the Town of Stanford, runs south into the Town of Northeast before winding back north through the hamlets of Bethel, Hammertown, and Patchins Mill in Pine Plains, then into Columbia County where it empties into the Roeliff Jansen Kill in Gallatin.

Grist Mills

A grist mill uses the energy from running water to power a water wheel, in which "grist" - corn, wheat, etc. that is ready for grinding - is ground into flour or meal by turning a large millstone. These products were used to make bread and many other staples. Cornmeal was used to make johnnycake and Indian pudding. The cob was separated from the corn kernels using a machine called a cracker, which is also how cracked corn was made.

The local farmer would bring his grain to the local mill for the miller to grind it for him. The fee for the miller's services was called a "toll" which was a portion of the grain brought for milling.

There were several grist mills in Pine Plains and its environs, usually situated near other kinds of mills. Many of these once-enterprising mills became cider mills in their final days, apples being in good supply in this area. Although cider was a popular beverage, cider vinegar was a kitchen staple.

The mills we know the most about are detailed here. The only one still standing is the one in the hamlet of Patchins Mill, but it is no longer in operation.

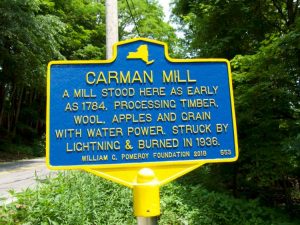

The Phineas Carman Mill

The Phineas Carman Mill, believed to date as far back as the 1740s, was on the Pine Plains - Amenia Road (County Route 83), about halfway between the hamlets of Bethel in Pine Plains and Shekomeko (not to be confused with the Native American village of that name) in North East. It is interesting to note that between municipal name changes and shifting boundaries, the mill site location changed multiple times over the years without it ever physically moving. It began in North East Precinct in the Little Nine Partners Patent, then "moved" to Crum Elbow Precinct, then Amenia Precinct, then the Town of Amenia, then the Town of North East, all within the Great Nine Partners Patent.

Lot 14 of the Little Nine Partners Patent went to James Graham in the deed of partition, but the Grahams soon discovered that what was on paper did not necessarily translate into physical possession. That's because the southern part of the lot, which is where the mill was located, was in "the Gore", a hotly contested wedge-shaped strip of land between the Little Nine and Great Nine patents which the patentees of both fought over for half a century (see "The Little Nine Partners Patent" page). In those days, possession was nine-tenths of the law. Johannes Rau of Moravian fame may have built the mill in the 1740s during the brief period he possessed Gore Lot, No. 3. Then in 1768 Joseph Harris, who owned land in the Great Nine (possibly the same Harris who was the scythe-maker, uncle of John Harris), took possession of the mill by putting a fence around it "in the night". The Grahams struggled for years to reclaim it. It wasn't until 1789 that James Graham's son Augustine was able to regain possession by suing to evict the current squatter, Coonrad Smith, and then requiring Smith to take out a lease on the property. The terms of the lease were for an annual rent of one hundred twenty bushels of wheat, twenty to be ground "toll free" and payment of all taxes. However, Augustine was only able to hold onto the mill for a short time, and Huntting discusses the ongoing legal battles over ownership in his history.

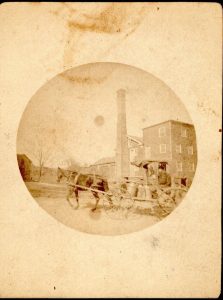

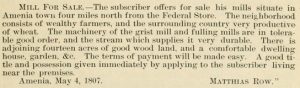

When the mill was put up for sale in 1807, a notice was placed in a Poughkeepsie newspaper (see inset).

The mill came into the Carman family when Richard Carman purchased it around 1816. Phineas Carman (1786-1875), who the mill is named for, was Richard's son. The Carmans were Quakers who attended the meeting house in Bethel. Phineas' son John was the last of the Carmans to own the mill (see "People" page for information on the grandson of Phineas, Isaac P. Carman). After being in the Carman family for sixty-three years, in 1879 it was sold to Walter Loucks for $2520.

The mill was later named the "Enterprise Mill" and was used to produce cider before it finally ceased operation. In 1936, the mill was struck by lightning and burned.

This was also the site of a fulling mill and a sawmill. The fulling mill was in use only from 1796 to 1807.

Click on the photo at right to watch "Making History", a video from Stan Hirson of Pine Plains Views about the dedication of the Pomeroy Foundation historical marker for the Carman Mill, June 22, 2019.

Click on the photo at right to watch "Making History", a video from Stan Hirson of Pine Plains Views about the dedication of the Pomeroy Foundation historical marker for the Carman Mill, June 22, 2019.

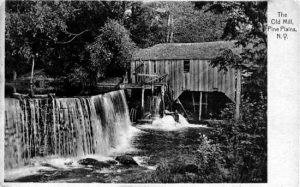

Patchins Mill (Hoffman's Mill)

The Shekomeko Creek ½ mile north of the hamlet of Pine Plains was recognized for its potential as a mill site at the time of the Little Nine Partners Patent survey in 1743, when surveyor Charles Clinton noted in his field notebook that the stream here "had fall fit for a mill". Arabella Graham, sister of Lewis Graham of the Graham-Brush House, later inherited this property from her father James Graham.

In 1801 Henry Hoffman purchased the property with his brother Matthias and built the grist mill which came to be called Hoffman’s Mill. In 1807 Henry bought out his brother’s share. Beginning in 1816, the mill was rented for many years by Thomas H. Chase.

The original mill had an undershot wheel. In 1840, a new mill was built on the same site with a turbine wheel. Mark Patchin, a millwright, installed the machinery and constructed many of the wooden fittings. In 1873, Mark bought the mill and house from Henry Hoffman’s grandson Anthony Hoffman Jr.

Besides grinding wheat, rye, buckwheat, and corn, the mill was also used to grind gypsum from Nova Scotia into plaster for fertilizer. The gypsum was brought to Barrytown on the Hudson River and from there by ox carts and wagons to the mill site. Farmers also brought grain to be ground into feed for cattle and horses.

The current mill building was built in 1917 and was the third mill built on this site.

The trade name of the mill was Shekomeko Stream Mill. The market for flour was from Boston to Chicago, with buckwheat in particular demand, and at one time, the mill was run round the clock, with day and night shifts. However, as the country moved west so did the manufacture of flour, and farmers here in the East stopped raising wheat. Demand for buckwheat also fell off, and buckwheat production at Patchins Mill ended in 1920. The mill closed completely in 1945.

There were three dams built at the mill site. The first one was made of logs, the second of stones and lumber, and the third of cement and stones. This third one was built in 1917 and still stands today.

The mill stands on the north end of the dam, and on the south side was a sawmill (long gone). Logs were brought in at the top of the hill south of the sawmill and rolled down the hill. A straight up and down saw was used to cut the logs.

There was also a carding mill northwest of the grist mill built in 1840. It was run by race water from the grist mill.

Click on the photo below to watch "This Old Mill", a video from Stan Hirson of Pine Plains Views, to see the inside of the mill and learn more about how it worked:

Carding and Fulling Mills

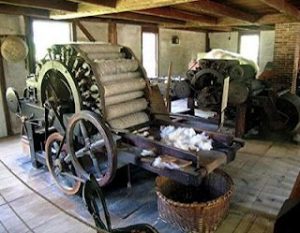

Carding was the first step in the process of transforming wool into a finished cloth product that could be worn. It was the act of brushing wool to make yarn and was mechanized in the late 18th century. After mechanization, carding mills began popping up all over.

After carding, the yarn was spun or woven at home and then the cloth was brought to a fuller to be shaped (made fuller), cleansed, and dyed. Fulling, also called "cloth dressing", had been mechanized for centuries.

Besides the mills already mentioned, a carding mill was built in 1815 by Isaiah Dibble on his farm in the hamlet of Bethel. A dam was built at the bend of the Shekomeko west of the iron bridge and a race cut along the bank northerly to the fulling mill, where cloth dressing was done by Jonathan Young in the 1820s. The industry was profitable for a time, but soon after Isaiah's son Abraham took over the farm in 1837 he took down the mill.

Another fulling mill was built down the Pine Plains - Amenia Road by the Samuel Deuel farm around 1830. A race was cut adjoining the highway to intersect the Shekomeko nearly opposite the grinding works, and the water for the power taken from there to the mill.

Factories and the use of other materials for cloth gradually began replacing the need for the little carding and fulling mills all over the countryside.

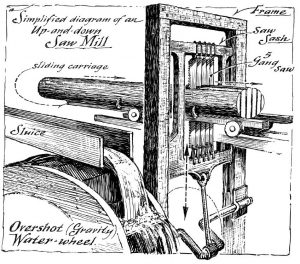

Sawmills

Sawmills were very important in early America. Lumber was needed to build bridges, dams, houses and buildings, wagons, caskets, furniture, and other products.

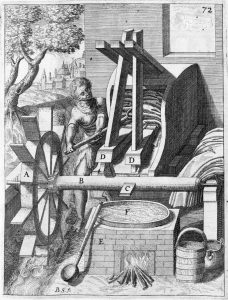

Sawmills were a lot faster and less labor-intensive than two men sawing a log using a saw pit, which is how it used to be done. Some of the earliest sawmills utilized an up and down saw or multiple saws like in this diagram (see inset); this is the type of saw described in use at the Patchins Mill sawmill. Starting around 1830, we begin to see the introduction of the circular blade.

Harris Scythe Works

The use of scythes as an agricultural tool for cutting grass and grains goes back to the ancient Romans. A long, curved single-edged blade is attached to a long wooden handle.

Harris Mill (Willowvale Mill)

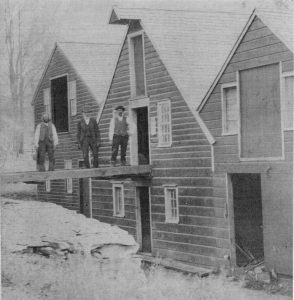

When John Harris first came to Pine Plains in 1783 from Andrus Rowe Corners where he had hand-forged scythes in his uncle Joseph Harris' blacksmith shop, he settled in Willowvale (Willowvale Road today). Here he set up his own scythe-making shop and also operated a sawmill. Four years later he purchased the grist mill. The 1867 Beers Atlas map shows a plaster mill here in place of the grist mill.

Here is a YouTube video showing how a blacksmith might have forged a scythe in his shop in the 19th century, with a trip hammer as well.

Hammertown

As demand increased, the scythe works were moved downstream to what soon became known as Hammertown, and around 1810 John was joined in this enterprise by Joseph's son Seth Harris and others. After the death of John Harris in 1814, Seth’s sons, Silas (“Colonel”) and John, joined the family business.

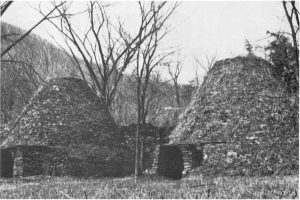

Charcoal was a very important part of this whole manufacturing process. For one thing, it is 65-70% fixed carbon and burns hotter than wood. It was produced by carbonization through the controlled burning of wood in an earthen mound or a kiln, located, for expediency, in a forest clearing. The resulting charcoal was then transported and fed into the blast furnace at the Ancram Iron Works along with iron ore and limestone to produce pig iron, a transportable ingot of impure high carbon-content iron. The iron works were located just to the north of Pine Plains in Columbia County.

Steel for making the scythes was purchased from the Wassaic Steel Works in the Town of Amenia. The pig iron was carted from the Ancram Iron Works down to the Steel Works where it was refined and carted back to Hammertown.

Around 1814 the first trip hammer was added in the manufacture of Harris scythes, semi-automating the process. By around 1816, 6,000 scythes were being made here annually. Silas bought land on Stissing Mountain so he would have a ready supply of wood to make charcoal to feed the fires of his furnace at the scythe works.

Printed labels like the one pictured here were pasted on each scythe. Silas Harris was engaging in a little false advertising in using the year 1776, however, since any Harris scythes made before 1783 were made in Joseph Harris’ shop in Andrus Rowe Corners. Apparently Silas liked the idea of his business being founded in the year of the country's independence even if it wasn't quite accurate. It is also said that Joseph Harris made bayonets for the Continental Army, so perhaps Silas wanted to be able to claim a piece of that history for his business as well.

To meet demand, Silas erected a grinding works on the Pine Plains-Amenia Road, a short distance from the Phineas Carman Mill. A prodigious amount of grinding the blades was necessary, and unfortunately this process was very detrimental to the grinder's health, exposing him over time to lethal amounts of silica dust.

Colonel Silas Harris died in 1862 and although the business continued for a few more years under his partner Jonas Knickerbocker, its best years were behind it. In 1831 Cyrus McCormick had invented a horse-drawn reaping machine, which was later followed by the combine harvester, making scythes obsolete.

At its peak, the Harris Scythe Works produced 18,000 scythes a year.

Cornelius and Peter Husted Tannery

A tannery was the other major industry in Hammertown. In early America, the creation of leather from animal skins was a crucial part of life, and Dutchess County led the state in tannin production.

An acidic chemical was necessary for tanning hides. This was usually derived from tree bark, hemlock being the preferred species. Peeling bark was grueling, seasonal work, and the peelers often set up camps right in the forest where they lived for the entire season. To simplify stripping the bark and turning the logs, trees were often felled into lakes, from which they could later be extracted for milling. Perhaps this was done here in Pine Plains. However, the trees were often just left to rot where they fell, as hemlock was not a desirable construction wood. The industry was also a heavy polluter, as used tanning liquid would be dumped right into the streams.

The Hammertown tannery was established in 1796 across the highway from the scythe works by Peter Husted, who named it for himself and his son, Cornelius. For about one hundred years, Hammertown was no doubt a noisy, foul-smelling place, between the incessant sound of the trip hammers at the scythe works to the aroma from the tannery operation.

Eventually, other sources of acidic chemicals were developed that worked just as well as plant materials in the tanning process, and the old tanneries closed. The Hammertown tannery closed sometime in the 1880s, and the factory was used for awhile as a cooperage business by John Duxbury. Around 1900, the buildings were taken down.

Sources and Suggested Further Reading:

History of the Little Nine Partners, by Isaac Huntting, Chas. Walsh & Co., Amenia, NY, 1897

The Department of Environmental Conservation Public Fishing Rights: "Shekomeko Creek"

The History of Dutchess County, ed. by Frank Hasbrouck, S. A. Matthieu, Poughkeepsie, NY, 1909

History of Columbia County, New York, by Capt. Franklin Ellis, 1878

The History of Flour Milling in Early America, by Theodore R. Hazen

Gray's Grist Mill: "How the Mill Works"

Paper on Patchins Mill in the LNPHS collection, written by Claire Robinson, 1973

Historical Echoes of Chemung, New York: "Carding and Fulling"

Hawthorne Valley Farmscape: "Charcoal Pits"

"Historic Charcoal Production in the U.S. and Forest Depletion", by Thomas J. Straka

200 Years of Soot and Sweat: "Historical Overview of Charcoal Making"

Colebrook Historical Society: "Charcoal's Role in the Iron Industry"

Scientific Research Publishing: "Charcoal as a Fuel in the Ironmaking and Smelting Industries"

Northern Woodlands: "Hemlock and Hide: The Tanbark Industry in Old New York"