It helps to first understand what a patent was before learning about the Little Nine Partners Patent. To do that, we will begin with a few words on the colonization of New Netherland under the Dutch in the 17th century. We will wrap up this page with the formation of the Town of Pine Plains in 1823.

The Dutch Patroonships

The Dutch West India Company, a chartered trading company, was behind the creation of New Netherland in 1621, mostly to stake a Dutch claim to the North American fur trade. However, settlement of the colony was slow, so in 1629 the company gave its investors permission to establish something they called patroonships as a means to promote settlement. A patroonship was a deeded grant to a large tract of land that had some vestiges of the feudal manorial system of medieval Europe. For example, the patroon, or landholder of the patroonship, possessed significant rights and privileges, such as the right to establish courts and appoint officials with jurisdiction over his patroonship, and the right to hold the land in perpetuity for himself and his heirs. The patroon was in return beholden to the Dutch West India Company: he had to purchase the land from the Indians and settle fifty colonists on his land within four years, and at his own expense. Although some of these settlers bought their land, most became tenant farmers on what are called leaseholds (see below), required to pay the patroon rent in money, goods, or services for a certain period of time on a piece of property they could never hope to own. The patroons provided some services for their tenants, such as mills and schools, but they also controlled many aspects of their tenants' lives, and if the tenant wanted to be released of his lease agreement, he couldn't simply walk away. By some accounts, the tenant farmers were a poor lot, little better than indentured servants.

The patroonship system failed, mostly due to mismanagement and difficulties dealing with the Dutch West India Company. There were also Native American raids to contend with. The only patroonship that succeeded and in fact lasted after the English takeover of the colony was Rensselaerswyck, which is Rensselaer County today.

The English Manors and Patents

The Dutch surrendered New Netherland to the English in 1664. King Charles II gave the colony to his brother James, the Duke of York (hence its new name the Province of New York); as proprietor of the colony, James had full governing rights. Once James became king in 1685 it became a royal colony.

The English made their own attempts at promoting settlement of the colony, using a system of political patronage. They called their version manors. The patroonship of Rensselaerswyck thus became Van Rensselaer Manor, or the Manor of Rensselaerswyck.

Under the manorial system, the royal governor granted vast tracts of land to wealthy individuals as a means of buying and rewarding political favor. In many ways, the manors were just a continuation of the patroonships. Most of these lands were developed as income-producing leaseholds. A manor grant included the honorary title of lord and in some cases a permanent seat for the landowner on the Colonial Assembly. The title may have been just honorary with no connection to English nobility, but just look at this portrait of Robert Livingston (see inset) -- what do you think he thought of himself?

The English also issued royal patents, sometimes called "crown grants". These were large tracts of land that were granted by the Crown to individuals, partners, or companies. The patents were less feudal in nature than the manors. With the exception of speculators out to make a quick profit, most patentees intended to hold these lands as leaseholds. However, a leasehold gave a slow investment return, and many of these patentees, weighed under with debt, gradually sold off their parcels to pay off their creditors.

Before any grant could be made, interested entrepreneurs would petition the governor for a license to buy the desired tract of land from the Indians. In the Little Nine Partners Patent, this was done in 1702. The tract had to be "unappropriated", that is, vacant. However, uncultivated or uninhabited land had a different meaning for Native Americans than it did for Europeans, not to mention the concept of land ownership. Also, these Indian deeds tended to have vague language when specifying boundary landmarks. This was intentional: the grants ended up being significantly larger than what was in the original deeds, showing us that this was nothing more than a fraudulent land grab attempt by the prospective landowners.

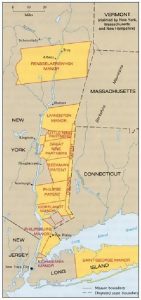

Manor or patent, the result was the same: the concentration of large blocks of land and power in the hands of a few, some of whom had never even set foot on their tract. These land grants operated under the principle of primogeniture, where the oldest son in each successive generation would inherit the estate, thereby keeping it intact for a hundred or more years. In Dutchess County alone you had the ownership of 806 square miles issued to less than 40 men. However, by the early 18th century, some of the more feudal aspects of the manors began to disappear.

There were fourteen patents issued in Dutchess County, including the Oblong Patent and the Philipse Patent which was split off in 1812 to form Putnam County (see inset). Since there were no manors in Dutchess County, the rest of this page will focus on land development as it pertained to the patents rather than the manors, although as already seen there were features they had in common.

A Multi-step Process

The order of tasks in this process could vary slightly from patent to patent.

With the land supposedly free and clear of Indian claims, the letters patent for the Little Nine Partners Patent was issued on April 10, 1706 by Secretary of the Province of New York, George Clarke. It was confirmed on September 25, 1708 by the Deputy Secretary of State, Anson S. Wood. This 18,000 acre tract was one of the last patents to be granted in Dutchess County. Among the terms of the grant, the patentees were given three years in which to settle the land and make improvements. But before taking their land, the patent had to be surveyed and partitioned into lots.

Here is where the process often stalled. Surveys were very costly; it was a time-consuming and often dangerous job. Sometimes it took years after a patent had been granted before the survey was done. This was one of the factors in the slow progress of settling Dutchess County.

In the meantime, no title could be given to the land, and anyone who settled on the patent was a squatter with no legal rights to it. This was actually a common occurrence. Another thing that often happened before the land was surveyed was for patentees to sell or reassign their shares, or portions thereof. The problem transactions were the partial conveyances, since at this stage, a patentee did not own specific tracts of land, just a right to a share; for example, if there were eight patentees, then each had a right to a one eighth share of the patent. This could get messy real fast. Not surprisingly, none of these transactions held.

The Colonial Assembly passed an act authorizing the partition of the Little Nine Partners Patent in 1734, and it took another nine years to the spring of 1743 for the patentees to engage the services of Charles Clinton, the deputy colonial surveyor. During that thirty-seven year span from the time of the issue of the letters patent in 1706, many of the original patentees had died and their heirs or other assignees would have to be determined. Also during that time: Palatines from the failed naval stores venture had entered the area and illegally settled on patent lands; Mahicans from the native village of Shekomeko had been to New York City to complain to the governor about their lands being overrun by settlers; Moravians had established their mission at Shekomeko; and patentee Richard Sackett had surveyed and sold (ostensibly with the blessing of the other patentees) three hundred acres which were to somehow come out of his share, to settler John Tice Smith (this did not hold).

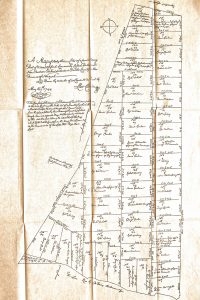

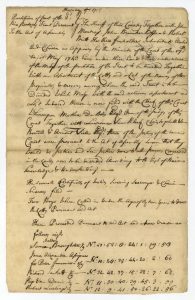

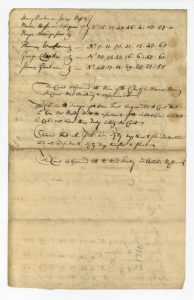

Charles Clinton completed the survey by November of 1743 and divided the tract into sixty-three lots. The resulting map of numbered lots is dated May 7, 1744 (see inset above) and encompassed land in what would become the towns of Pine Plains and Milan and part of the town of North East (and also part of the towns of Clinton and Stanford if we include the Gore -- see below for that discussion). The Dutchess County Court subsequently convened to draw the lot assignments for each shareholder (see insets below). By this time, the number of shares had grown to nine with the addition of George Clarke, who had not been a patentee. Each shareholder received seven numbers in the lottery, and their names were added to the corresponding numbered lots on the map.

The lot numbers were drawn by "two boys under the age of sixteen", sixteen being the age that a boy became an adult, so anyone younger was a child and therefore to be considered impartial and beyond reproach.

The Deed of Partition is dated October 19, 1744.

The Little Nine Partners Patent is sometimes called the Upper Nine Partners Patent. It was so-named to distinguish it from an earlier, larger patent to its immediate south which also had nine partners. The earlier patent was originally called the Nine Partners Patent, which then became the Great Nine Partners Patent, sometimes called Lower Nine Partners Patent.

Leaseholds versus Freeholds

There were two types of colonial land tenure. Fee simple, or a freehold, was the most common and most absolute type of land ownership, where a piece of property was purchased outright for an indeterminate length of time. The owner was called a freeholder.

Nothing came for free, however, and all landowners (from the common freeholders to the lords of the manors and the patentees), were required to pay an annual land tax to the Crown (after the Revolution to the State of New York), called a quit-rent, another feudal holdover meaning that after payment the landowner was free for a year of further obligation. Initially these were nominal or payable in kind such as in bushels of wheat, but later they increased and became important sources of revenue, although notoriously difficult to collect. For the patentees of the Little Nine Partners Patent, the quit-rent was three pounds. The quit-rent system was finally abolished by the state legislature in 1821 by the payment of arrears to the state treasurer. When on March 4, 1823 Reuben W. Bostwick, town clerk of North East, paid off the $17.01 owed to the state for the 21 lots in arrears in North East, the quit-rent came to an end in our locality. Today, we have property taxes, which owe their origin to the quit-rents of this bygone time.

The other type of land tenure was the leasehold, held by virtue of a lease. Lease terms varied and were controlled by the landlord. Under a leasehold, the leaseholder, or tenant, bought the right to occupy a piece of property for a predetermined length of time. Unlike a short-term lease (i.e. annual), these leaseholds were perpetual, or multi-generational (99 years was common), which meant that the leaseholder had a status similar to a farmer who owned his land outright, and it was common to pass the lease down through subsequent generations of the tenant's family. The leaseholder had to pay certain taxes besides rent. The landlord owned the land and any buildings on the land, but leaseholds could be bought and sold, however the landlord usually reserved a cut of the sale for himself.

Most of the Little Nine Partners Patent lots started out as leaseholds, but little by little most of the partners or their assignees subdivided their lots and sold these parcels off. The one notable exception was George Clarke's Lot 47, which was located on the west side of what is Main Street in Pine Plains today, north and south of the intersection with Church Street. Lot 47 remained intact for 154 years until the end of the 19th century, passed down in the Clarke family and maintained as leaseholds.

Did the leaseholds delay land development?

On the assessment roles of 1737, there were only 13 white head of households living in North Precinct (the precursor to North East Precinct), comprising the future towns of Pine Plains, Milan, and part of North East. It is still debated how much of a role leaseholds played in this delayed development.

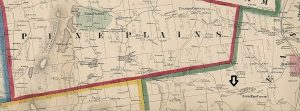

We have a unique opportunity to see how Clarke's Lot 47 was settled via the testimony provided by detailed 19th century maps. This 1876 map of Pine Plains hamlet (see inset) shows how the west side of Main Street, which was Lot 47, is significantly undeveloped compared with the east side which had been Graham lots that were sold off and allowed to develop as freeholds. The west side is characterized by temporary structures such as wagon shops, livery stables, and blacksmith shops, or nothing at all. There were exceptions: for example, the Stissing House (called Myers House on the map) was a leasehold on this lot. But it wasn't until Lot 47 was finally subdivided in 1895 and the parcels sold at auction that the development of this tract got underway. This was such big news that it was even written up in the New York Times.

While in 1737 the slow development could be explained by geography, lack of good roads, and a patent not yet surveyed, the map shows that the leasehold system was still affecting the development of Pine Plains over a century later, after these other factors had ceased being an issue.

An un-American system

There is no doubt that, all things considered, most settlers would prefer being a homesteader on a freehold to being a tenant on a leasehold.

A leaseholder owned a right to occupancy, not the land itself. He was always at the mercy of the landlord's whims. Landlords could change the terms of the lease, or increase revenues while cutting back on services, such as the construction of gristmills and sawmills. Some landlords replaced perpetual leases with annual leases, which meant tenants lost the proprietary rights to land improvements that had been one of the perks of the long-term leases. Many of these tenants, like squatters, felt that property rights should be based on occupancy and labor. They felt that the leasehold system was aristocratic and un-American, something akin to taxation without representation.

One may ask why anyone would become a tenant on one of these leaseholds. Well, for some farmers the cash required for a down payment on a freehold made that option unattainable. Also, some of the landowners had figured out that they could lure tenants with lucrative deals which expired years down the road. Part of the reason the leasehold system lasted as long as it did was because once a farmer became a tenant on a leasehold it was difficult to leave, even for his future generations.

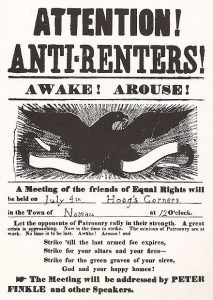

Eventually, disgruntled tenants, particularly on the manors, banded together in protest. These protests were known as the anti-rent wars, which came to a head in the 1840s and finally led to real land reform. While this was never a problem in Pine Plains, it does deserve mention.

The Gore

The Gore, as it pertains to the Little Nine Partners Patent, was so-called because it was a disputed strip of border land between the Little Nine patent and the Great Nine patent to its immediate south. It was, however, not the only "Gore" of disputed territory in colonial Dutchess County.

Our Gore had its origin in 1734 when Richard Edsall did his survey of the Great Nine Partners Patent, beginning at the head of Fish Creek (Crum Elbow Creek) in the west, and proceeding due east to the Oblong on the Connecticut border. Some of the Great Nine patentees felt that Edsall's northern line was too far south, leaving too much land in play for the Little Nine patent which had yet to be surveyed. So, a few years later these Great Nine patentees hired another surveyor, Jacobus Bryuyn (Brown). However, Brown's northern line was further south than Edsall's, which meant a third survey was in order. This was done in 1740 by Jacobus TerBoss (also called Judge Bush). His line was north of Edsall's. Then in 1743 Charles Clinton did his survey of the Little Nine patent. His Little Nine southern line ran between the Edsall and Brown lines, in effect laying the bottom half of the southern Little Nine patent lots right over a portion of the northern Great Nine patent lots as surveyed by Edsall and TerBoss. The wedge of land created by the TerBoss and Clinton lines was The Gore, spanning ten rods over a mile and a half.

[Note: Huntting's account of the Gore issue is very confusing and contradictory. His claim that the Clinton line was the south-most survey line, south of the Brown line, is not supported by the 1858 town map (insert below). The town and patent maps provided invaluable primary sources for our own analysis of the surveys for this page.]

Four surveys, all beginning in roughly the same place, with four different results. The most likely explanation for the discrepancies was that this was either a land grab by the Great Nine partners, or their attempt to forestall a real or perceived land grab by the Little Nine partners, helped along by instrument or human error. Who was in the right? After all this time, it is impossible to know.

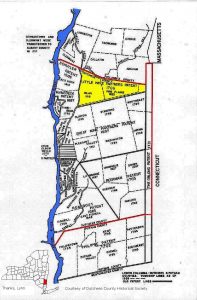

The Great Nine Partners Patent map (see inset) shows the lines of the three Great Nine surveys along its northern boundary. The Brown line, which is marked, is dotted because it was never considered seriously. The solid line above it is the Edsall line, and above that is the TerBoss line. Additionally, TerBoss surveyed the Gore (that is, the land between his line and Edsall's) and divided it into four lots. Both Edsall and TerBoss's names and the dates of their surveys are on the document in the upper right.

This was not going to be resolved overnight. In fact, it was the cause of decades of land disputes, one of them being over the Carman mill (see "Industries Along the Shekomeko" page).

Ultimately, as the various precincts and then towns were divided and their boundaries agreed upon, the Edsall line was allowed to stand, which meant that Pine Plains lost out on claiming about half of Little Nine Patent Lots 9-18 along its southern border. Today, this once hotly disputed land is within the towns of Clinton, Stanford, and North East.

This detail of an 1858 Dutchess County map (see inset above) shows the town boundaries with an overlay of the patents. You can see where the southern boundary of the Little Nine patent is in relation to the Brown line (the line just below it with the arrow pointing) and also in relation to the present town boundary (highlighted in red and green).

Meet the Little Nine Partners

The patentees of the Little Nine Partners Patent were the original company of men who were granted the patent. There were eight patentees: Sampson Broughton, Rip Van Dam, Thomas Wenham, Roger Mompesson, Peter Fauconier, Augustine Graham, Richard Sackett, and Robert Lurting. George Clarke bought a ninth share later on and thus became the ninth partner, but he was not a patentee.

The Little Nine partners were not the wealthiest group of men; the wealthiest of them was probably George Clarke. Most were of the merchant class. Many were patentees of other patents as well. Some were even a little crooked. However, overall they presented a pretty impressive resume. Sampson Broughton was the son of the Attorney General of New York, Sampson Shelton Broughton. Rip Van Dam was an influential Dutch merchant. Thomas Wenham was also a merchant, a receiver of customs in 1702 and associate judge of the Supreme Court. Roger Mompesson was Chief Justice of New York and New Jersey (but paying off his father's debts reduced him to poverty). Peter Fauconier was a French naval officer, but as receiver of customs from 1702-1707 was caught stealing from the treasury. Augustine Graham, the Surveyor General of New York and son of Attorney General James Graham, had a noble bloodline: he was the great-grandson of the Marquis of Montrose of Scotland. Richard Sackett was a brewer and early settler in the region; he was put in charge of the Palatines who were brought over to New York to make naval stores. Robert Lurting, called Colonel, was a merchant who got himself in a bit of trouble for allegedly selling goods unlawfully while he was Vendue Master (auctioneer) of New York City. George Clarke was English and appointed Secretary of the Province of New York and later, acting governor; he married into the English royal family.

(for more on Augustine Graham, Richard Sackett, and George Clarke, see the "People" page).

As of 1741, Rip Van Dam, Peter Fauconier, Richard Sackett, Robert Lurting, and George Clarke were the only surviving nine partners.

When the patent was partitioned in 1744, the heirs or assignees of those who had died had to be determined. These are their names on the partition map: James Graham (for Augustine Graham); James Alexander (for Peter Fauconier); Henry Beekman, Isaiah Ross, and Martin (Martinus) Hoffman (for Roger Mompesson). However, Thomas Wenham had died in 1709 but he was still on the deed of partition. Also, in 1733 Robert Lurting had sold his share to Robert Livingston, Jr. and the sons of Rip Van Dam, Richard and Isaac Van Dam, but his name was still on the deed of partition.

It was a man's world

Most colonial governments operated under the same laws as the mother country. Colonial white women living under Dutch rule in New Netherland, like their compatriots back in the Dutch Republic, had more autonomy, more rights, and more income than most other European women of their time.

Once the English took over New Netherland and the colony gradually converted to English Common Law, the status of women changed, but not in a positive direction. While single women and even widows had many of the rights and privileges of men, for example, they could independently enter into contracts and buy and sell real estate, such was not the case once a woman married. Since England was a more strictly patriarchal society than the Dutch Republic, married women lost much of the autonomy they had enjoyed under the Dutch. It must have been particularly difficult for Dutch women who now had to live under English law, where, among other restrictions, a married woman had no control over her personal property (such as money) without the consent of her husband. Everything that was hers was now his to do with as he pleased.

However, married women had some protection when it came to real property, whether it was property the husband or wife had brought individually into the marriage, or property they had acquired together. For example, a wife had to consent to any conveyance of real property by her husband, and this authorization went right in the contract. On the 1749 deed of sale for a portion of Lot 12 from Isaac Van Dam, an assignee of Robert Lurting, to John Tice Smith, both Isaac's and his wife Isabella's signatures and wax seals are plainly visible. However, there is something less visible but equally important, at least for Isabella. A paragraph in small writing at the bottom of the deed (on the reverse) effectively states that Isabella has been questioned apart from her husband, and that she has agreed to the sale and has entered into the contract of her own free will.

The formation of the Town of Pine Plains

The Little Nine Partners Patent first fell under the civil jurisdiction of North Precinct when the precincts were created in 1737, then North East Precinct in 1746, then the Town of North East when that was established in 1788. The area of what is Pine Plains today, because of its central location, was the seat of government for this vast tract. From early on it was called "the pine plains" because of all the pine trees that grew on the glacial outwash plains at the foot of Stissing Mountain.

Gradually the difficulties of having a seat of government that covered such a large area and which was so remote from its western and eastern borders became too burdensome. So, in 1818, the western portion of North East split off and formed the Town of Milan. Then the central portion split off and the Town of Pine Plains was formed on March 26, 1823, with the first town meeting held on April 1, 1823.

Here is the text of the law establishing Pine Plains:

“An Act to Divide the Towns of Northeast and Amenia, in the County of Dutchess,” (March 26, 1823). Laws of the State of New York passed at the forty-sixth session of the Legislature 1823, Albany: Leake and Croswell, pgs 101-102

Ch 86

An Act to Divide the Towns of Northeast and Amenia, in the County of Dutchess,

Passed March 26, 1823

(Town of Northeast Divided)

- BE it enacted by the People of the State of New-York, represented in Senate and Assembly,That from and after the last day in March in the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty-three, all that part of the town of Amenia, in the county of Dutchess, lying north of a certain line beginning on the division line of the state of Connecticut, and the said town of Amenia, at a monument, being a corner, between lots number sixty and sixty-two of the oblong; running thence westerly on the dividing line of the said lots, to the end thereof; thence continuing the same course across the said town of Amenia, to the east line of the town of Stanford; thence northerly on said line, to the south line of the town of Northeast; thence easterly on the south line of Northeast, on the north side of the gore, to a hard maple-tree, standing on the west side of the highway, on the line between the heirs of Elijah Roe, deceased, and Nathan E. Conklin; thence northwardly to the southeast corner of the dwelling house of Samuel Russell, leaving the said dwelling-house in the westerly town; thence due north to the south line of Columbia county; thence easterly to the west line of the oblong; thence northerly on said line to the southwest corner of the state of Massachusetts; thence easterly on said line to the state of Connecticut; thence southerly on said line of Connecticut, to the place of beginning; shall be, and hereby is, erected into a town, by the name of Northeast; and the first town meeting be held at the house of Alexander Neely, in said town, on the first Tuesday of April next.

(Town of Pine Plains Erected)

- And be it further enacted,That all the remaining part of the town of Northeast, shall be, and remain a separate town, by the name of Pine Plains; and the next town meeting shall be held at the house of Israel Reynolds, in said town; and that all the remaining part of the town of Amenia, shall be and remain a separate town, by the name of Amenia; and the next town meeting shall be held at the house of Thomas Paine, in said town.

(Monies and Poor Divided)

III. And be it further enacted, That as soon as may be, after the first Tuesday in April next, the supervisors and overseers of the poor of the towns of Pine Plains, Northeast, and Amenia, notice being first given for that purpose, shall meet together, and divide the money and poor, belonging to the towns of Northeast and Amenia, agreeable to the last tax list, and that each of said towns shall, forever thereafter, respectfully maintain their own poor, excepting the monies now in the hands of the commissioners of highways, of the town of Northeast, heretofore raised for the support of bridges, in the said town, of which fifty dollars shall be paid to the town of Northeast, and the remainder, shall belong to the town of Pine Plains, for the use of said town.”

The name of the town was taken from the Pine Plains Post Office, which had already been established in 1819, whose name in turn had come from the common name for the region.

The following were the first officers of the new town: Israel Harris, town supervisor; Reuben W. Bostwick, town clerk; and Samuel Russell and Isaac Sherwood, overseers of the poor.

Sources and Further Reading:

Hudson River Valley Institute: "Colonial Land Grants in Dutchess County, New York", by William P. McDermott

History of the Little Nine Partners, by Isaac Huntting, Chas. Walsh & Co., Amenia, NY, 1897

The Origin and History of the Manors in New York and the County of Westchester, by Edward Floyd De Lancey, New York, 1886

The Quit-Rent System in the American Colonies, by Beverly W. Bond, Jr., New Haven, 1919

Jacobin Magazine: "When the Serfs Rebelled", by Ed Burmila

"History of Dutchess County", edited by Frank Hasbrouck, published by S.A. Matthieu, Poughkeepsie, NY, 1909

Church Family Website: "Early History of Rensselaer County", by Craig Stromme

"Perceptions of Property in the Hudson Valley", by Thomas J. Humphrey

"A Factious People: Politics and Society in Colonial New York", eBook preview, by Patricia U. Bonomi

"The End of the Hudson Valley's Peculiar Institution: The Anti-Rent Movement's Politics, Social Relations, & Economics", by Eric Kades

Little Nine Partners Patent Index to Deeds and Mortgages, compiled by Clara Losee, Milan Town Historian, ca. 1970

Places of Little Nine Partners: "The Little Nine Partners Patent"

History of American Women: "Dutch Women"

University of Nebraska Dept of History: "A Widow's Will: Examining the Challenges of Widowhood in Early Modern England and America", by Alyson D. Alvarez