"LAND ACKNOWLEDGMENT: We acknowledge that the land presently referred to as Pine Plains, NY is the occupied, unceded, seized territory of the Schaghticoke-Mahican Peoples, and we pay respect to their elders, past and present, who have stewarded the land since time immemorial. We are committed to learning the history of these people to better understand how we might eliminate their erasure and to support the current cultural and land stewardship missions of their living descendants."

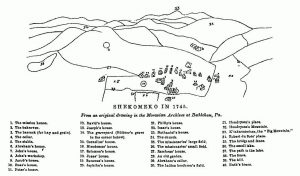

The establishment of the Moravian mission at Shekomeko in the 1740s remains the single most important event in Pine Plains history. It is also probably the least understood.

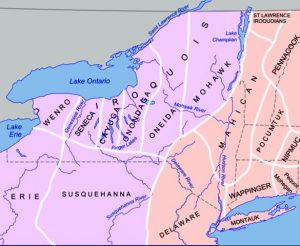

Before the Europeans, this area was home to an Algonkian-speaking Eastern woodland people, the Schaghticoke-Mahicans (hereafter for simplicity referred to as Mahican). The Mahicans are not to be confused with the Mohegans of eastern Connecticut.

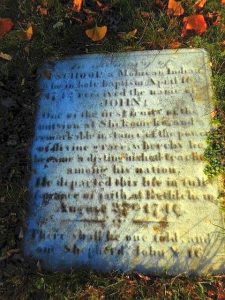

Today, a few historic markers and the monument at the intersection of Strever Farm Road and Bethel Cross Road are all that remain to remind us of their one-time presence in Pine Plains. We also have a few words of Algonkian origin that have been incorporated into the English language, such as muskrat, opossum, skunk, and chipmunk, and some place names such as Poughkeepsie, Stissing, and Shekomeko. The meaning of the name “Shekomeko” has been translated variously as “the place of eels”, “little mountain”, and “a great clearing”. There are also two different pronunciations: SHEE-ko-MEE-ko (how the Moravians say it) or sheh-KOM-e-ko (how the locals say it).

What happened to the Mahicans?

In 1609 Henry Hudson, in the employ of the Dutch East India Company, sailed up the river that would bear his name looking for a northeast passage to India. Henry Hudson didn’t find the northeast passage, but he did find the area abundant with fur-bearing animals, and fur was in high demand in Europe. Life for the Mahicans would never be the same.

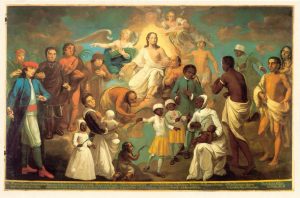

European explorers operated on the idea that they had a God-given right to claim indigenous lands they “discovered” in the New World (this so-called “Doctrine of Discovery” is only recently being repudiated by national churches). By 1614, based on Hudson’s findings, the Dutch had established a strong foothold in the region, building several trading posts and forts up and down the river, and in 1624 the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam was established. By 1628, the Dutch were also in the business of granting large tracks of land, called patroonships, as special favors to wealthy patrons.

The Mahicans soon found themselves in competition with their enemies to the north, the Mohawks, over the fur trade with the Dutch. The region became destabilized, pushing the Mahicans further south and east.

In 1664, the English invaded New Amsterdam and the Dutch surrendered their colony, which was renamed the Province of New York. In 1683, Dutchess County was founded.

While the Dutch had exploited the land mostly for trade, the English wanted the land for itself. Like fur, land was a commodity to be bought and sold. The Dutch had not been successful in promoting settlement of their colony, however the English fared little better, at least initially. In 1706 the Little Nine Partners Patent became one the last patents in Dutchess County to be granted, encompassing the area that would become the town of Pine Plains as well as Milan and part of North East. But for the next thirty-seven years, until the patent was surveyed, the land lay undivided and unable to be assigned to any of the patentees. One reason for this delay was because surveying such a large tract of land was an expensive and time-consuming task.

(see "The Little Nine Partners Patent" page for more on the patent and on colonial land development)

In 1710, the English brought Palatines over to the colony to work on the production of naval stores (the tapping of pine trees for gum which could be distilled to make tar, pitch, turpentine, and resin, used in the weather-proofing of ships). The Palatines had emigrated to England for various reasons from a region in Germany called the Palatinate, and were not really welcomed in their adoptive home, so this was a way for the English to basically get rid of them and hopefully make a lot of money in the process. However, the venture was a complete failure and halted in 1712. The Palatines dispersed throughout the region, with some settling in the Pine Plains area. This was the first real influx of Europeans into our area. However, because the patent was not yet surveyed, any would-be settlers were squatters with no legal claim to the land.

The earliest non-Native American house that we have any record of in Pine Plains, later called the Dibblee-Booth House, was a log structure located west of the center of the present Pine Plains hamlet and operated as an Indian trading post. It is believed to have dated from 1728.

As of 1730, four-fifths of Dutchess County was still not opened for development. Part of this was because of the lack of good roads, but it was also because of the slow progress in surveying the patents. In the meantime, some patentees went about selling and re-assigning their shares anyway, but these transactions were not legally binding. The scene was being set for years of land disputes.

To complicate matters, Native American and European views of land ownership differed. To the Indians, land was a shared resource held in communion, and tribal ownership was determined by tradition, not by courts of law. Because they moved seasonally, there could be long periods where the land stood vacant and uncultivated. Europeans assumed any uninhabited land was available for white settlement. Even where Europeans attempted to legally purchase native land, determining boundaries made this difficult.

In 1738, three Mahican dignitaries from the native village of Shekomeko in what became Pine Plains brought their grievances over land issues before the governor in New York City. The Indians were concerned about the settlers overrunning their land. The governor recommended that they should mark off a square mile of land they wished to keep (which they never did) and promised them they would be paid for any other land once the patent was surveyed. On a similar visit to New York City in 1740, Sachem (Chief) Shabash and Tschoop from Shekomeko met Moravian missionary Christian Henry Rauch. The timing was perfect: Rauch, direct from Germany and all of twenty-two years old, was looking for an opportunity to preach to the Indians, and the Shekomeko Indians were receptive to him. Rauch arrived at Shekomeko on August 16, 1740, where he established a mission. Other Moravian missionaries soon joined him there.

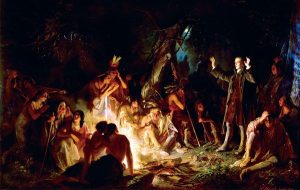

The Moravians were the first large-scale Protestant missionary movement, and the first to send lay people rather than clergy as missionaries. In fact, the Moravians were unique in that they lived among the Mahicans and adopted their lifestyle, which allowed for a mutual trust to develop between the two groups.

By this time the Mahicans were an oppressed people. Their numbers had been diminished by years of exposure to new diseases brought by the Europeans and by war with other tribes. Their culture had been destroyed by years of participation in a barter economy with the Europeans, which relied on their women making wampum instead of farming and their men hunting fur-bearing animals instead of deer. This and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle (ironically facilitated by mission life) meant less land was being cultivated, which could lead to a dietary condition called nutritional stress. While selling alcohol to Indians was illegal because they were alcohol-intolerant, local traders often bartered alcohol for native land anyway. This bit of trickery was wide-spread at Shekomeko, exasperating the Mahicans’ land problems. Finally, as the Mahicans became divided over those who favored the traditional lifestyle and those who favored assimilation, they began to lose their sense of identity.

Still, things were quiet on the frontier between whites and Indians for the moment, and as long as the status quo was maintained the settlers tolerated the Mahicans’ presence. Then along came the missionaries. At first, the Moravians were accepted by their white neighbors, and the bark mission church, which is credited as the first house of worship in Pine Plains, was used by whites and Indians alike. The missionaries even taught the local settlers’ children.

The “first fruits” (first converts) of the Moravian Mission at Shekomeko were Abraham (formerly Shabash, appointed elder), Jacob (formerly Kiop, appointed exhorter), Isaac (formerly Seim, appointed diener), and Johannes (formerly Wasamapah/Tschoop/Job, appointed teacher). All except Tschoop were baptized on Feb 11, 1742 in Oley, Pa.

Tschoop couldn't make the journey to Pennsylvania with the others because an injury had left him lame. Instead, he was baptized at Shekomeko on April 16, 1742 by Rauch. Tschoop was the "Owl," the right hand man and advisor of Sachem Shabash, and is believed to be the model for Chingachgook in James Fenimore Cooper’s “The Last of the Mohicans."

In August of 1742, Count Zinzendorf, Bishop of the Moravian Church, visited the little mission at Shekomeko and formed what is considered to be the first Christian congregation of Native Americans in present-day United States, consisting of 10 people. But the initial goodwill between the missionaries at Shekomeko and the settlers soon began to deteriorate. As a foreboding of things to come, Count Zinzendorf himself was arrested and fined for breaking the Sabbath (an infraction the authorities usually turned a blind eye to) on the return journey to Bethlehem from Shekomeko.

What happened to cause this?

It's complicated, but fear of the Moravians and the Indians, and greed for the land, were the primary factors. No one really knew who the Moravians were. Clergy of other denominations treated them with disdain, and they were often confused with the Jesuits, Catholic missionaries who had been banned from the province. The Moravians’ religion forbade them swearing any kind of oath or serving in the military, and this made many locals suspect their loyalty at a time when settlers on the frontier were very nervous over the French threat from nearby Canada. The settlers were also becoming uneasy with the relationship that was developing between the Moravians and the Mahicans. For one thing, the Mahican converts abstained from alcohol, and alcohol had been very important to the settlers in their dealings with the Indians: intoxicated Indians were less inclined to attack, and could be more easily swindled out of their land. One gets the sense that the settlers felt that if they could just get rid of the Moravians things could go back to the way they had been with the Mahicans.

Then in 1743 the survey of the patent was finally completed. The land was now available for legal settlement, and the settlers would be able to buy the land they had been squatting on. But first the patent had to be divided up into lots which were assigned to the original patentees or their heirs (as due to the length of time which had passed, some of the patentees had died). This process was begun in 1744.

It was then noticed that one of the patent lots ran right through land claimed by the Mahicans. With the help of the Moravians, the Mahicans drew up a petition of names of people who could attest to this being Mahican land. This action certainly did not endear the Moravians to many of their white neighbors, and the Mahicans ultimately lost their case. But the petition illustrates that not all the settlers were against the Moravians and out to steal the Mahicans’ land. For example, the Palatine John Rowe (Johannes Rau) who lived near Shekomeko remained a good friend of the Moravians and his daughter, Jeannette, married missionary Martin Mack. Jeannette knew the native language and assisted as a translator for the missionaries.

(see "People" page for more about the players in this drama)

As things escalated, some of the settlers began arming themselves and spreading rumors that the Indians were planning to attack, and they kept watch to prevent further visits of Moravians from Bethlehem. Meanwhile, the Moravians at Shekomeko began to be systematically harassed by the authorities in Poughkeepsie. In November 1744, the governor ordered all Moravians to “desist from further teaching and depart the province.” In February 1745 two Moravian missionaries, David Zeisberger and Christian Friedrich Post, were arrested for disloyalty to the government and thrown into prison in New York City. Moravians from the headquarters in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania made repeated attempts to intervene in these persecutions, but without success. A May 21, 1745 entry in the Moravians’ Bethlehem diaries states that, “Martinus Hoffman let the Brethren [Moravians] at Checomeko know that they should not take anything from their house that is attached or nailed down. He is one of the partners who are taking over the land of the Indians and everything built upon it and pretending it is theirs.” [Martinus Hoffman was an assignee of one of the original partners of the Little Nine patent, Roger Mompesson, who had died in 1715.]

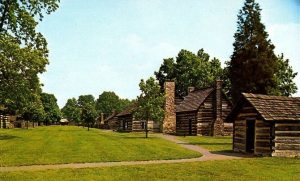

After hysterical settlers demanded a warrant for killing the Shekomeko Indians (which was not granted), the Moravians made the difficult decision to abandon the mission. The exodus began in 1745, as the missionaries along with ten Mahican families, including Tschoop, left Shekomeko for Bethlehem (Tschoop would die here of smallpox in 1746) and Gnadenhutten in Ohio. Some Indians chose to ride it out and stayed in Shekomeko for a time, while others joined the Mahicans in Stockbridge, Massachusetts or the nearby Wechquadnach and Pishgatgoch Moravian missions in Millerton NY and Kent CT. While most of the Stockbridge descendants today live on the Stockbridge-Munsee Reservation in Wisconsin, where they were relocated in 1822 as part of the federal removal policy, there are Schaghticoke-Mahican descendants still living in this area.

The Shekomeko mission officially closed on July 25, 1746.

So what happened next? Well, in 1746, the same year that the mission closed, the settlers established their own church about a mile from the former mission site which they named Round Top (also called Nine Partners).

In 1749 the British Parliament recognized the Moravian Church as a legitimate Protestant sect and exempted them from having to take oaths. This of course came several years too late for the Moravians at Shekomeko. However, in 1753, eight years after the demise of the mission and four years after this parliamentary act, a Moravian from Bethlehem, Abraham Reinke, was invited to come and preach at the Round Top Church while visiting area missions. This may seem odd until we remember that not all of the settlers had partaken in the persecution of the Moravians and their Indian converts, and this invitation was probably extended by those who had befriended the missionaries.

In 1763 a Royal Proclamation was finally issued that to some degree protected the rights of Native Americans. Colonists were forbidden from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains and any colonists already there were ordered to remove themselves. Why was this done now? Because most Algonkian tribes had sided with France during the recent French and Indian War, and the English Crown was looking for ways to stabilize the frontier and reduce the cost of colonial defense. However, the colonists were outraged by it, and it is one of the many issues that led to the American Revolution just over ten years later.

Sadly, Pine Plains forgot what happened at Shekomeko, as after a few years no trace of the mission or village remained. Then in 1854 a clergyman from Pleasant Valley, The Rev. Sheldon Davis, who was studying the Moravians, together with a local farmer, Josiah Winans, determined the location of the mission and the final resting place of Gottlieb Büttner, one of the leading missionaries who had died of tuberculosis at Shekomeko in 1745 (Büttner is credited with writing the first hymn in Mahican, “Jesu paschgon kia” (“Jesus, to you alone”) at Shekomeko in 1744). In 1859, the Moravian Historical Society and local dignitaries dedicated a monument at Büttner’s gravesite, seen today at the intersection of Strever Farm and Bethel Cross Roads, to the memories of Büttner and Lazara and Daniel, two baptized Mahicans.

The monument was moved to its present location in 1918 to facilitate the cultivation of farmland.

Büttner’s gravesite is lost to history.

Sources and Suggested Further Reading:

Out of the Wilderness, a LNPHS publication

A History of the Beginnings of Moravian Work in America, The Rev. William N. Schwarze and the Rt. Rev. Samuel H. Gapp, The Archives of the Moravian Church, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1955

The Bethlehem Diary, Vol. I, trans. and edited by Kenneth G. Hamilton, The Archives of the Moravian Church, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1971

The Bethlehem Diary, Vol. II, trans. by Kenneth G. Hamilton and Lothar Madeheim, edited by Vernon H. Nelson, Otto Dreydoppel, Jr., and Doris Rohland Yob, The Archives of the Moravian Church, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 2001

The History of the Moravian Mission Among the Indians of North America, by George Henry Loskiel, London: T. Allman, 1838

A Memorial of the Dedication of Monuments by the Moravian Historical Society..., by W. C. Reichel, J.B. Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia, 1860. (includes the pamphlet "Shekomeko" by The Rev. Sheldon Davis)

Martyrs of the Oblong and Little Nine, by DeCost Smith, The Caxton Printers, Ltd., Idaho, 1948

Gideon's People, 2-Volume Set: Being a Chronicle of an American Indian Community in Colonial Connecticut and the Moravian Missionaries Who Served There (book preview), trans. and edited by Corinna Dally-Starna and William A. Starna, University of Nebraska Press, 2009, copyrighted by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation

Tears of Repentance: Christian Indian Identity and Community in Colonial Southern New England, by Julius H. Rubin, University of Nebraska Press, 2013

To Live Upon Hope: Mohicans and Missionaries in the Eighteenth-Century Northeast, by Rachel Wheeler, Cornell University Press, 2013

Valerie LaRobardier, Schaghticoke First Nations.